|

First

posted: 7-09-01

On the night of February 6, 1954, in the lower intestines

of Manhattan, two homeless people, an aging, booze-addled

poet and his young, unstable wife, sought shelter from

an impending late winter storm. The idea of yet another

night spent sleeping on park benches—no matter how

swaddled with alcohol and newspapers the two might have

been—was too painful to bear.

Then the pair crossed paths

with an off-duty dishwasher, with whom they were acquainted

from the bars of the Village. The dishwasher had the hots

for the old poet's wife—who did little to discourage

his interest—and offered to share his room on the

fifth floor at 97 Third Avenue with them. Numb from cold

and booze, the trio managed, with their suitcases, bottles

of wine and other potables, to make it to the dingy walk-up

flat. The old poet was offered the bed, a glorified cot,

where he flopped, pulled out a book and commenced reading.

He seemed as at home here on this strange, fetid mattress

as anywhere else in the world.

The young wife and dishwasher

continued drinking. Soon enough, they began groping on

the floor, then rutting like demented goats not more than

an arm's length from the cot on which the old poet was

thought to be sleeping. But the old poet had noticed their

state of arousal and challenged the dishwasher. Much younger

and stronger, he overpowered the old man and shot him

twice in the chest (appropriately, right in the heart).

The old poet died instantly. With his young wife screaming

bloody murder, the dishwasher plunged a hunting knife

into her back four times. After a struggle she also died,

her body grotesquely twisted in her final agonized moments

on the floor. As the killer left the blood-drenched, completely

ransacked room, he locked the door from the outside.

The cops didn't come until

the next afternoon, when the rooming house proprietor

asked them to break the padlock because he was owed back

rent (apparently the sound of a struggle and a gun going

off twice didn't attract curiosity from the other tenants).

On a table near the bed, the cops found some scribbled

poems, a pad of paper and pen and an empty liquor bottle.

Propped up against the table was a hand-lettered sign

that said "I Am Blind," which Bodenheim was

said to use to beg for money on the streets. When the

identity of the poet was discovered and released to the

press, the details of the crime dominated New York newspapers

for days. The killer was easily apprehended soon thereafter;

he confessed to the crime but was deemed mentally incompetent

to stand trial.

The murder was the final,

seemingly inevitable chapter in the life of one of New

York's literary legends, the author of 10 books of verse

and 13 novels, as well as a partly ghost-written memoir

called My Life and Loves in Greenwich Village.

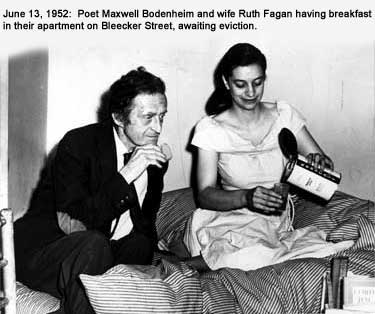

The old poet's name was Maxwell Bodenheim, age 62; he

had once been king of the Greenwich Village bohemians.

Bodenheim's 35-year-old "wife"—it was never

clear whether they were legally married—possessed

the Dickensian name Ruth Fagin (alternately spelled in

the papers as "Fagan" or "Fagen").

The 25-year-old killer

was officially named Harold Weinberg, although he was

known around the Village as "Charlie." Described

by Life magazine as "a wild-talking, scar-faced

vagabond," the truth was that he may have been mildly

retarded, even schizophrenic and that he was tolerated

by the legendarily non-judgmental Villagers who saw him

around the neighborhood. The murders gave him a sudden,

perverse fame, and he basked in it, describing the grisly

events of February 6 to the police and scandal sheets—just

as they’re recounted here. In lieu of facing the

two murder charges, Weinberg, aka "Charlie,"

was sent to a mental institution.

In the 1920s, when Greenwich

Village was in full flower, Maxwell Bodenheim was known,

even to unhip middle Americans, as the living embodiment

of bohemian existence. He'd inherited the mantle from the

late John Reed who, before he became the playboy-revolutionary

depicted in the film Reds, was the "golden boy"

of Greenwich Village. Indeed, Reed's poem The Day in

Bohemia, or Life Among the Artists (1912) was perhaps

the first open declaration that America had its own thriving

"Left Bank."

Reed, a Harvard graduate

so prodigiously gifted that his renowned mentor, Lincoln

Steffens, told him "you can do anything," chose

the carefree life of the artist and applied his writing

talents to documenting it. His verse, a mirror image of

his own jeu d'esprit, echoed Joycean wordplay and presaged

early Beat poetry, with everything from guttersnipes to

high society names, faces, bars, bistros, people, streets,

bookshops, stray chat, shouting matches, howls, moans,

shouts of glee: "Inglorious Miltons by the score,/

Mute Wagners, Rembrandts, ten or more/ And Rodins, one

to every floor./ In short, those unknown men of genius

who dwell in third-floor rears gangrenous,/ Reft of their

rightful heritage/ By a commercial soulless age./ Unwept,

I might add, and unsung,/ Insolvent, but entirely young."

The poem went on in this manner for thirty-five pages.

When Reed died in Moscow

in 1920, Max Bodenheim, who had just moved to New York,

willingly picked up Reed's banner. A prolific poet, novelist,

provocateur and performer, as well as an inveterate womanizer,

the handsome and self-promoting Bodenheim was known to

millions for his willful embrace of all things unconventional.

"He personified the avant-garde," wrote Life.

"He was young and slim with sandy red hair and pale,

baleful blue eyes, and women jammed tiny candlelit rooms

in the Village when he gave readings of his poems."

His personal history was

shrouded by sometimes-artful mystery. Bodenheim—known

as "Bogie" or Max to friends—variously

identified his birthplace as Mississippi, Missouri or

Illinois and his birthdate as 1893 and 1895. (The truth

is that he was born in Hermanville, Mississippi on May

26, 1892.) His family moved to Chicago in 1900, and when

he told his shopkeeper father that he wanted to be a poet,

the idea did not sit well. They quarreled, and the enmity

increased when Max was expelled from high school. The

prodigal son left home to hop freight trains in the Southwest

(or so he claimed), but soon joined the U.S. Army. He

was in the Army from 1910 to 1913 but was dishonorably

discharged after a stint in the Fort Leavenworth brig

for going AWOL and—so again he claimed—for bashing

an anti-Semitic officer over the head with a musket.

Upon his release from prison,

Max drifted back to Chicago with a suitcase full of poems,

rejection slips and a bottle of Tabasco sauce. While his

self-created myth was that he was an outcast living totally

on his wits, Max actually moved back in with his mother

and father. This aspect of his life, hidden from his Chicago

literary comrades, was later revealed in his 1923 novel

Blackguard. This was a thinly veiled autobiographical

account of the prodigal son's inauspicious return to face

his mother, embittered for having fallen from her social

station, and his father, embittered over failed business

ventures. Even with a roof over his head and free board,

Max still found much to alienate him in the city, describing

his family's apartment as "standing like a factory

box awaiting shipment, but never called for."

Max lucked into a friendship

with a tolerant circle of writers that included Harriett

Monroe (founder of Poetry, a driving force for

the American "poetry renaissance"), Margaret

Anderson (editor of the highly influential Little Review)

and Ben Hecht, a newspaperman and playwright with a penchant

for bohemianism. Hecht was particularly impressed with

Bodenheim's literary talents. He ignored Max’s abhorrent

personal habits—he seldom bathed, cadged food and

drink like every meal was his last, stole small items

to pawn, made passes at any woman and tongue-lashed anyone

who tried to thwart his impulses—and the two spent

many evenings collaborating on plays and poetry.

Hecht and Bodenheim performed

their work at the Dill Pickle Club, a renovated barn on

Chicago's Near North Side that was open to any and all

political, artistic and intellectual persuasions. The

pair pulled off one particularly memorable prank, declaring

a debate on the topic "Resolved: People Who Attend

Literary Debates Are Imbeciles." A full (paid) house

attended this "debate," which consisted of Hecht,

who was arguing the affirmative position, announcing:

"the affirmative rests." Bodenheim strode on

stage. His rebuttal consisted of: "You win."

End of debate, to much angry shouting from the audience.

In his memoir Letters

from Bohemia, Ben Hecht reports a typical tempestuous

exchange with Bodenheim:

Max: "Nobody seems

to like me. Do you think it is because I am too aware

of people's tiny hearts and massive stupidities?"

Hecht: "They are too

aware of your big mouth. Why don't you try ignoring their

imperfections, after sundown?"

Max: "I was born without

your talent for boot-licking."

Hecht goes

on to describe how Bodenheim "crowed with delight

and whacked his thigh... it is this strut I remember as

Bogie's signature. Ignored, slapped around, reduced to

beggary, Bodenheim's mocking grin remained flying in his

private global war like a tattered flag. God knows what

he was mocking. Possibly, mankind."

* * *

In 1918, Bodenheim

married Minna Schein. She inspired his first, and some

would argue best, book of poems, Minna and Myself,

published that same year. They moved to Greenwich Village

in 1920, at which point Bodenheim picked up the mantel

from the late John Reed.

It was at this time that

Bodenheim established a pattern, which would remain until

his violent death in 1954. That is, he had an odd sort

of charisma that attracted women upon whom he could rely

for free food, board, clothing, sex—all the while,

he was legally married to Minna (until their divorce in

1938).

As Emily Hahn, author of

an "informal history of bohemianism in America,"

put it in 1967, "Many a reporter is still living

who can look back to Bogie's banner year, 1928, when it

seemed for a while as if no week could pass without some

distracted female trying to kill herself for the love

of him."

She cites the case of 18-year-old

Gladys Loeb, who briefly lived with Bodenheim. When he

rejected her, she went back to her room, turned on the

gas and, with a photograph of Bodenheim clutched in her

arms, lay down to die. But the landlord saved her in time.

Her father, a Bronx doctor, came to fetch her from the

bohemian purgatory into which she'd fallen and swore vengeance

against Max (who left town until the whole thing blew

over). Next was Virginia Drew, an artistically inclined

22-year-old. When he rejected her, Drew threw herself

in the East River and drowned. He had dismissed her poetry,

which she had asked him to critique, as "sentimental

slush."

Soon after, a woman named

Aimee Cortez, a mentally imbalanced Village "character"

known for her nude dancing at parties, decided to emulate

Gladys Loeb. She turned on the gas, clutched a photograph

of Bodenheim to her heart and died. A fourth jilted woman,

carrying several of his letters, was killed in a subway

crash.

From photographs of him

taken at this time and even into the 1930s, it's obvious

that Bodenheim had a certain dissipated sexiness. Most

images of him in the papers were of a hollow-cheeked,

slick-haired cock of the walk. In some photographs, Max

Bodenheim is almost a double for Pat Riley or young Michael

(or Kirk) Douglas.

Though his antics and excesses

were legendary, Max was amazingly prolific for one whose

personal habits leaned toward dissipation. He followed

Minna and Myself (praised by the likes of Carl

Sandburg, Conrad Aiken and William Carlos Williams) with

several more well-received volumes of poetry, including

Advice (1920), Introducing Irony (1922),

The Sardonic Arm (1923), Against This Age

(1925) and Returning to Emotion (1926). His was

the perfect poetic backdrop for the profligate Jazz Age,

especially in America's largest and culturally most important

city. Still, Bodenheim was unknown outside bohemian or

avant-garde circles. This lack of popularity did constant

battle with his buoyant sense of himself as a suffering

genius.

Williams, never one to

suffer posers, was frank but admiring of Max in a 1920

essay: "Bodenheim pretends to hate most people...

but that he really goes to this trouble I cannot imagine....

I know of no one who lives so completely in his pretenses

as Bogie does.... Because of this he remains for me a

heroic figure, which, after all, is quite apart from the

stuff he writes and which only concerns him. He is an

Isaiah of the butterflies."

Bodenheim's limited profile

changed with the 1925 publication of his third novel,

Replenishing Jessica, which made him an overnight

sensation. The novel, a candid exploration of a young

woman's sexual liberation among seedy bohemians, shocked

polite society but also hit the bestseller list. The reason

for its popularity, according to Hahn, was that it "had

the good luck to be condemned as obscene." In fact,

the protracted (and ultimately unsuccessful) obscenity

trial inspired New York Mayor Jimmy Walker to quip, "No

girl has ever been seduced by a book."

According to historian

Allen Churchill in The Improper Bohemians, a classic

study of Greenwich Village in its heyday, Bodenheim, after

this, "seemed to face few obstacles on his path to

literary triumph." He was lavishly, even over-extravagantly,

praised by the likes of Louis Untermeyer ("words

under his hands... bear fantastic fruit") and Burton

Rascoe ("the Rimbaud of the arts, a remarkable and

gifted poet").

Among his other notorious

novels were Naked on Roller Skates (1930) and New

York Madness (1933). The former featured a woman who

wanted to live with "an A number one, guaranteed

bastard [who will] beat my heart and beat my brain...

and lug me to... the lowest dives." The latter traces

the quest of "two bright, vivacious New York girls"

and their "fierce craving for excitement" that

takes them to the East Side, the waterfront dives, Union

Square and "the racketeer hells on the Broadway sidestreets,"

not coincidentally the places that the author regularly

frequented.

Once the scandals cleared,

Stanley Kunitz defended the novels: "Bodenheim is

not a pornographer; he is deadly earnest, and there is

an evangelistic tone to all his novels, in spite of their

wild humor. The keynote of all his work is hatred, hatred

for meanness and dirt and cruelty, and sometimes, it seems,

hatred for humanity itself... he was one of the pioneers

in bringing naturalism of the French school into American

writing."

Despite all this notoriety

and sudden influx of cash, Bodenheim possessed what he

called "a malady of the soul." After a legendary,

gossip-column falling out with Bodenheim, Hecht described

his erstwhile friend's "mystic sense of himself as

an unwanted one." Their falling out was over Hecht's

novel Count Bruga, about an eccentric poet said

to be based on Bodenheim.

Indeed, after the Jazz

Age sobered up to the Great Depression, Bodenheim's literary

popularity waned, but he did not stop writing. The combined

effect of the Depression, his dependence on booze, the

official break-up of his first marriage and the increasing

queasiness of former friends to have anything to do with

him was the inevitable decline. Max Bodenheim was like

a fading comet on a precipitous plunge across the night

sky. By the 1940s, his vision of bohemianism was found

mostly in the bottoms of bottles. His resentful, alcohol-fueled

literary output was hard to read and of no particular

interest to an America now freed of the Depression's yoke.

He briefly broke his fall

with a second marriage in 1939 to Grace Finan, the widow

of a painter. He spent part of the year with her in the

Catskills, and she told Kunitz in 1942, "It's fun

to watch him in the country. He enjoys every leaf and

twig. We plan to make our permanent home in Catskill,

one of these days. He likes to roam the hills and raid

the orchards."

Soon after this, Bodenheim

broke with Finan (she died in 1950) and returned to the

considerably meaner streets of New York. He became a regular

habitue of the San Remo, a raucous bar at 93 MacDougal

Street, at the corner of Bleecker, that stayed open nightly

until 4 a.m. By then, he was a full-blown alcoholic and

a neighborhood "character" in the same league,

though not nearly as tolerated, as Joe Gould, the subject

of Joseph Mitchell's classic, Joe Gould's Secret.

Gould and Bodenheim, in fact, frequented the same Raven

Poetry Circle meetings, and they even began to physically

resemble one another.

Oddly enough, at the same

time that Bodenheim was hanging out in the San Remo, the

bar was the favorite watering hole of writers who would

become known as the Beat Generation—Jack Kerouac

and Allen Ginsberg, as well as painters Larry Rivers,

Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and unaffiliateds

like W. H. Auden, John Cage, Paul Goodman and Merce Cunningham.

Bodenheim appears in few accounts of these people's lives.

He was a pariah.

By then, according to one

old-time Villager, Bodenheim was "a pest.... If you

saw him coming, you crossed the street."

His favorite shtick was

to sell his poems in bars and restaurants (the ones he'd

not been banished from). Because he was no longer capable

of writing, he reportedly bought poems from other Village

poets, a hundred at a time, and peddled them as his own.

When he had nothing to sell, he panhandled. When he got

enough money together, he drank himself into a stupor.

After each protracted bender, he ended up in Bellevue

Hospital. After one arrest in early 1952, for sleeping

in an empty subway train, he told Time magazine,

"The Village used to have a spirit of Bohemia, gaiety,

sadness, beauty, poetry.... Now it's just a geographical

location."

Leo Connellan, an aspiring

writer who later became Connecticut's poet laureate, met

Bodenheim in these latter stages of his life. Despite

Max's horrific habits, the then young Connellan viewed

him as a sort of mentor.

"At one time, he was

as good as anybody. He and St. Vincent Millay. I lived

in the Village then, in a $4 week room right off Charles

Street," said Connellan, who died in Connecticut

in February 2001. "Everyone knew Ruth. She'd gone

over to Dorothy Day Catholic Work Home on Staten Island….

Many times I went over there, too, to do farm work for

food and a place to sleep. We all thought Ruth was playing

at being bohemian. The original conception of the liberated

woman was of a Long Island housewife who came into the

city to screw 15 guys between Friday and Sunday and then

went back to the clothesline on Monday morning to be a

mom. That was freedom. Ruth came to the Village in that

wave and met Max. Max used to be at the Kettle of Fish

or Rienze, on the corner of Bleecker Street, and he was

always crocked out of his skull. He'd scribble something

on a piece of paper and sell it for 25 cents and he'd

buy drinks."

Hahn described him at this

time as, "A grotesque figure who had long since lost

his good looks, with cheeks fallen above toothless gums,

unshaven face and unspeakable clothes, he yet, at the

age of sixty, found a woman to marry him."

This would be Ruth Fagin,

whom he met in 1950. Fagin was presumed to be mentally

unstable, though she was a not unattractive honor graduate

of the University of Michigan who'd come to New York to

pursue a job in journalism. Before she found life on the

streets with Bodenheim in New York, she had worked at

the Washington Daily News, Newsweek and

(back in Michigan, where she was from) the East Lansing

News. Her job in New York was as a freelance manuscript

typist.

As Hahn describes it, "After

their marriage, Bodenheim and Ruth lived in the manner

to which he had become accustomed, cadging money or drinks.

Occasionally Ruth picked up men to sleep with, or Bogie

found them for her. The two stuck together. They fought

each other, cursed each other, but helped each other too,

sharing whatever dingy shelter they could find at night."

Connellan remembers the

situation differently:

"One day, I was working

for a guy named Johnny Romero as a frycook... and I was

walking up towards MacDougal Street. And my God there

was Max, he has pressed pants, a shirt and a tie on, and

it turns out Ruth had gone up to the 4th Avenue publishers,

gotten them to reprint Naked on Roller Skates,

Replenishing Jessica and Minna and Myself.

Max was always out of it. I also had a job then driving

cars across the country. The agency would give me $125

to use on the car, $100 of which was for me. And what

I'd do is sell seats in the car, go to the Riviera on

West 4th Street and announce, 'Hey, you want to go to

Texas? For $25, I'll take you and we'll share driving.'

Anyway, I was walking down

Sixth Avenue past where they used to have a Hayes Pickford

Cafeteria, where the unwritten rule was that if you were

broke and someone saw you, without saying a word, they

would buy you a bowl of thick pea soup and a couple pieces

of rye bread and that was your ticket. You could stay

there all day. The next time I'd see you in dire straits,

I'd go get you a cup of coffee and a bowl of soup and

some rye bread. It was an unwritten rule. Ruth came out

of the Hayes Pickford, and I said, ‘Well, Ruth, I'm

going to split town... it'll be about a week before I

see you and Max again.' She looked at me, 'Well at least

you could go and say goodbye to Max.' So I went in and

he was drunk. I sat down opposite him and I said, 'Max,

I'll see you next week.' He didn't hear me."

That, of course, was the

last time Connellan saw Max. But his remembrance of the

man accused of killing Max and Ruth was also different

than that portrayed in accounts that have been written.

"There was a guy on

MacDougal Street we called Charlie and Charlie was sort

of dimwitted, like the Lenny character in Of Mice and

Men. Everybody told Ruth, 'You want to cocktease guys,

go ahead, but leave Charlie alone, Charlie won't understand

you.' Anyway, I got to Galveston and picked up a newspaper

and the headline said, ‘Maxwell Bodenheim Murdered

in New York.’ When I got back, I went to see Will

Brady, a gay friend of mine, and he said, ‘Well Leo,

you know we all told Ruth if she wanted to trip that's

fine but not with Charlie because Charlie wouldn't understand

that she didn't mean it.’ And that's exactly what

she did. Ruth went into the Kettle of Fish, she cockteased

Charlie that night and got him to go with her and Max.

They went to a hero shop and got grinders and booze and

they went around the corner to the apartment."

"When they found Maxwell

Bodenheim," said Connellan, "he was sitting

on the bed with two bullet holes right through the copy

of Rachel Carson's The Sea Around Us that he had

been reading. Is that not a perfect image? Ruth, of course,

was decimated on the floor. Even the cops knew what really

happened that night. I think Charlie didn't serve but

five or six years."

The few historians who've

written about the rise and fall of Maxwell Bodenheim have

the last word, for now.

Emily Hahn succinctly put

his life in perspective this way: "Bodenheim's novels

were not immortal. It is for his life and death he is

remembered. These were lurid in exactly the fashion Philistines

felt they had a right to expect of Bohemians."

Jack B. Moore, the only

writer to attempt a biography of Max, wrote: "I believe

it true of Bodenheim's life and art that rarely has an

American writer of any historic significance committed

more obvious and sometimes disastrous mistakes: but it

is also true that rarely have the virtues and accomplishments

of such a writer been so clearly misrepresented and so

quickly forgotten."

More Best of

Gadfly:

Film:

Planet

of the Apes

Arousing

an Apathetic Audience

Women

Filmmakers

Celluloid

Rock

54th

Cannes Film Festival

Roger

Ebert's 3rd Overlooked Film Festival/David Urrutia Interview

Book:

Eudora

Welty

Grand

Dad Terry

Kalle

Lasn

Mad

Max

Gregory

Corso

Christopher

Hitchens

Eric

Bogosian

Art:

Venice

Biennale

Anais

Nin

Music:

Robert

Goulet

Karma

Is on My Side

The

Artist Not at All Known as Prince

Online

Band-aid

Merle

Haggard

Filling

Up on Ochs

Issues:

Marijuana

as Medicine

Footnotes

From the Book of Job

Great

Generation Hoax

Overnight

in Terre Haute

Abbie

Hoffman

|