Read part one here.

Because Shakespeare dedicated “Venus and Adonis” in 1593 and “The Rape of Lucrece” in 1594 to Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, and addressed him intimately in several of the sonnets, the Stratfordians inferred that the Earl was Shakespeare’s patron and possibly even his lover. But if Oxford was Shakespeare, then the relationship between the two peers takes on an entirely different significance. Wriosthesley was engaged to Oxford’s daughter Elizabeth from 1592 to 94, and though the betrothed couple didn’t marry, Oxford and Southampton remained friends and shared a mutual interest in the theatre (Looney 177-86). Nevertheless, Joseph Sobran believes some of the sonnets addressed to a young man, whom he assumes was Southamton, imply a homosexual relationship (Sobran 199-201), but Charlton Ogburn, Jr., disputes that theory, pointing out that de Vere had reason enough to feel “in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,” when “I all alone beweep my outcast state.” Instead, he speculates that Oxford was writing those sonnets to his son and heir, Henry (Ogburn 4).

As for the “Dark Lady” of the sonnets, again the Stratfordians aren’t very convincing. Her identity remained a mystery until in 1973, A.L. Rowse proclaimed he had discovered she was “Emilia Bassano, the promiscuous wife of William Lanier and mistress of Lord Hunsdon” (Tallmer). He even published a book of her poetry (Rowse). But if Shakespeare was de Vere, a more plausible candidate would be Anne Vavasor, a niece of Thomas and Katherine Knyvet who was appointed a Gentlewoman of the Bedchamber in 1580. Her affair with the twenty-nine year old Oxford produced a son, for which the furious Queen dispatched the illicit lovers to the Tower and kept Oxford there for two and a half months (Ogburn 610-613, 646).

The accurate dating of Shakespeare’s plays has yet to be fixed, so those that were published after Oxford’s death were most probably improved literary revisions of earlier stage versions. It’s interesting to note, however, that Oxford’s daughters and their husbands, the Earls of Derby, Montgomery and Berkshire, were connected with the First Folio of 1623 at every stage of production (Miller 1). Those six, with the probable addition of Oxford’s son, Henry de Vere, had every reason and the financial resources to gather together and publish Oxford’s plays in a single volume to be preserved for posterity (Brewster 196).

On the other hand,“During Shaksper’s entire life not one of his contemporaries ever referred to him as a writer. The only references to Shakespeare were to writings with which the name was connected., and none referred otherwise personally to a writer of that name. Thus neither in the writings themselves nor in their authorship is there anything whatsoever which identified the Stratford man with the author of any of the works, or identifies the two different names, Shaksper and Shakespear with each other” (McMichael 197).

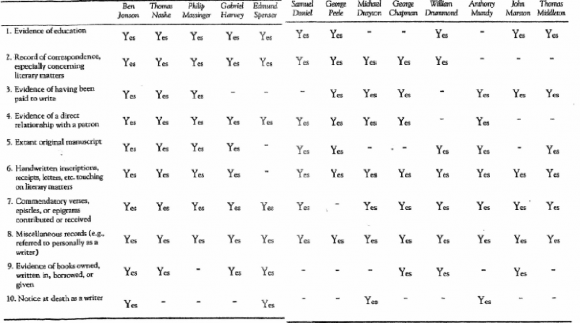

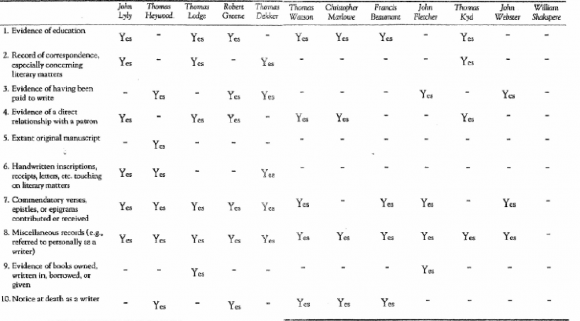

In her book, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography, Diana Price states that “stripped of conjecture and ancillary information…surrounded by phrases such as “might have,” “we have no doubt that,” “could have,” “it is likely that,” “doubtless” this and “doubtless” that,” most pages of any standard Shakespeare biography can be reduced to a few pages of actual facts (12). By comparing the recorded facts regarding Shakespere’s career as a writer to the “personal and literary records left by [two dozen] Elizabethan and Jacobean writers during their lifetimes,” Price convincingly proves that there is no factual evidence that William Shakespere of Stratford was a writer (301). She illustrates the results of her research by appending the following chart to her biography:

Appendix: Chart of Literary Paper Trails

Just as birds can be distinguished from turtles by characteristics peculiar to the species, so writers can be distinguished from doctors, actors, or financiers, by the types of personal records left behind. This chart compares personal and literary records left by Elizabethan and Jacobean writers during their lifetimes, with at least one record extant for any category checked. Category 10 includes evidence dating up to 12 months following death, to allow for eulogies or reports of death. Documentation follows (301).

(302-305)

But as it is impossible in a short paper to list all the evidence and coincidences linking de Vere and Shakespeare, if we compare some aspects of his life to the tragedy of Hamlet, the play most scholars agree is the closest we have to Shakespeare’s autobiography, it may suffice to persuade an open minded reader that Oxford may very well have been the real Shakespeare.

Edward’s father died when the youth was fourteen, and just as Hamlet’s mother remarried shortly after her husband’s funeral, de Vere’s mother also remarried rather hastily. Edward’s brotherinlaw visited the Danish court at Elsinore, and two cousins, named Horace and Francis, were probably the models for the characters of Horatio and Francisco. As a Royal Ward in the household of Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Edward was as close to the center of power and politics of Queen Elizabeth’s court as is Hamlet in that of King Claudius. If Polonius is a satirical portrait of Burghley, then Ophelia must have been drawn from Cecil’s daughter, Anne, whom Oxford married at twentyone. Because the Queen’s favorite, Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, was granted most of the 16th Earl’s lands when he died, Edward may have patterned the usurping Claudius after Dudley and the easily seduced Gertrude after Elizabeth (Ogburn 434).

Much of Hamlet’s suicidal soliloquy (III,i) has been traced to Cardanus Comforte, a book Oxford had translated into English and published in 1573 (Ogburn 526-28), and the Danish Prince’s capture by pirates while sailing to England (V,vi) happened to de Vere in 1576 when Dutch pirates set upon his ship in the Channel (556).

Two of Shakespeare’s favorite sources are Ovid’s Metamorphosis and the Bible. It seems more than a coincidence, therefore, that de Vere’s uncle and sometime tutor, Arthur Golding, translated Ovid into English (Ogburn 443), and that the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C., has Oxford’s Geneva Bible with his marginal notes and several verses underlined that are found in Shakespeare’s works (Stritmatter).

William Shakspere could scarcely sign his name. While he is alleged to have substantially increased the English vocabulary, his wife and daughters remained ignorant, incapable of reading his exquisite poetry. He made a will in January and then revised it on March 25, 1616. Leaving a certain amount of money and a silver gilt bowl to his daughter Judith, the father bestows all of his property and most of his belongings to his daughter Susanna and his “second best bed with the furniture” to his wife. No mention is made of his shares in the Globe theater and his house in Blackfriars, nor of any books and manuscripts. Shakspere died a month later, and the burial register of Trinity Church in Stratford contains this record: “April 25 Will. Shakspere gent. Even his physician son-in-law, John Hall, who once expressed an admiration for Michael Drayton’s poetry, was no more eloquent when he wrote in his diary “my father-in-law died on Thursday.”

How odd that when the greatest poet in England died, other than these two brief entries there is no mention of his passing. No tributes or eulogies, no ceremonies or memorials, nothing. All of London evidently didn’t know or were indifferent to the demise of their beloved Shakespeare. But six months after Oxford died on June 24th, 1604, “King James honored his memory by having more Shakespeare plays presented at court during the Christmas season than had ever been given in one short period” (Looney 299).

There are several reasons why the Strafordians remain stubbornly opposed to accepting Edward de Vere as Shakespeare. He is not the first candidate to be proclaimed as the real Shakespeare, so it’s to be expected that his claim to the title should be met with the same skepticism as were the others. Then there is the professional resistance on the part of the Shakespeare establishment. Too many reputations and tenured positions depend on the years of research devoted to the study of William Shakspere. And then there is his association with Stratford-on-Avon which is so essential to the tourist industry of Warwickshire. But as more and more evidence is discovered connecting the 17th Earl of Oxford with persons, places and sources that influenced Shakespeare’s poetry and plays, it becomes increasingly more difficult to deny his acceptance as the greatest poet in English and possibly in the world.

—

Fernando Valdivia is an adjunct Associate Professor of English at SUNY Ulster in Stone Ridge, NY. A former free lance drama reviewer for The Times Herald Record in Middletown, NY, his fiction and poetry have appeared in Bluestone Quarterly, Cadence, Esprit, The Glens Falls Review, Oxalis, Riverdreams and The Woodstock Review. A one-act play, Mary O’Connor, was performed at the Harold Clurman Theatre, 412 W. 42nd Street, NYC in 1996 by Love Creek Productions, and a full-length play, The Shunning, was published in 1997 by Eldridge Plays and Musicals. His 15-minute play, Welcome, was performed by Brief Acts Co., at the Creative Place Theatre, 750, 8th Ave., NYC., as well Skirt Job, a one-act comedy in 2004.

Works Cited

Brewster, Elizabeth. Oxford and His Elizabethan Ladies. Philadelphia: Dorrance and Company, 1972, p. 196.

Lardner, James. “Onward And Upward With the Arts.” The New Yorker April 11, 1988, pp. 93-96, 106.

Looney, J. Thomas. Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, 3rd edition. Jennings, Louisiana: Minos Publishing Company, 1975.

McMichael, George, and Edgar M. Glen. Shakespeare and his Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. New York: The Odyssey Press, 1962.

Miller, Ruth Lloyd. “The First Folio: An Oxfordian Family Affair.” Shakespeare Articles, 1975, pp. 1-3.

Ogburn, Charlton. The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality, 2nd edition. McLean, Virginia: EPM Publications, 1992.

Prechter, Robert R., Jr. “Verse Parallels between Oxford andShakespeare.” The Oxfordian, Volume XIV, Web 2012. http://www.shakespeareoxforfellowship.org

Price, Diana. Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2001.

Rowse,A.L., editor. The Poems of Shakespeare’s Dark Lady: Salve Deus Rex Judoeorum by Emilia Lanier. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc./Publishers, 1979.

Shakespeare Authorship FAQ. Online. Web 20 June. 1997. Available: http://www.Shakespeare-Oxford.com.

Sobran, Joseph. Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary _Mystery of All Time. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

Stritmatter, Roger and Mark K. Anderson. “Shakespeare’s Bible Brings Truth to Light.” The Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter Fall 1996. Web 20 June 1997.

Tallmer, Jerry. “He Gets a Kick Out of Shakespeare.” New York Post Jan. 6, 1979.

One thought on “Will’s True Quill Pt. 2”

Comments are closed.