The year 2014 brings yet another twelve months of hyperbolic, and over stimulated cinematic spectacle. Following a year of Superhero re-hashes (Man of Steel), comic book adaptations (Kick-Ass 2, The Wolverine), darker themed sequels (Thor: The Dark World, Star Trek: Into Darkness) and over indulgent science fiction (After Earth, Pacific Rim), it seems Hollywood has lined up another round of expensive eye-candy. I recently had the pleasure of watching The Hobbit: Desolation of Smaug at the cinema, although I firmly place this film in the same category of over produced films listed above, its fantastical charm was difficult to ignore. Though it was punctured with action sequences as mindboggling and disorientating as any modern blockbuster, the films satisfaction emerged from the continuing narrative arc, and of the dwarfs and hobbits venturing across rich and dramatic landscapes. However, the forthcoming trailers that preceded The Hobbit were an array of CGI glorification. The trailers in question, Edge of Tomorrow, Jupiter Ascending, Divergence and Captain America: The Winter Solider, played out like an eight minute long advertisement in preparation for the end of the world, directed at an audience who have been weaned on effects-laden cinema and crammed narratives. Nowadays a film trailer cannot allow a potential audience time to think and feel, but must throw as much debris at them in order for something to stick. One forthcoming film trailer that you will doubtfully see playing before any of the films above is an experimental documentary film called Manakamana. Despite its numerous awards and nominations, and its thoughtful and passionate reviews, the film will unlikely play to mass audiences. Although I have yet to see this movie myself, its short trailer of an elderly man and, I assume, his young grandson sitting silently side by side, as they ascend a mountain in a cable car towards the Manakamana Temple in Napal, quenches a humanistic thirst, and provides a composure that is constantly missing from modern cinema. The film’s quiet and calm is virtually alien in our modern times of fast paced editing, bombastic sound, and attention grabbing antics, and I await a screening of the film with anticipation. Until then, however, I am running blind, and my musings are based on the trailer alone.

Click here to see the trailer for Manakamana.

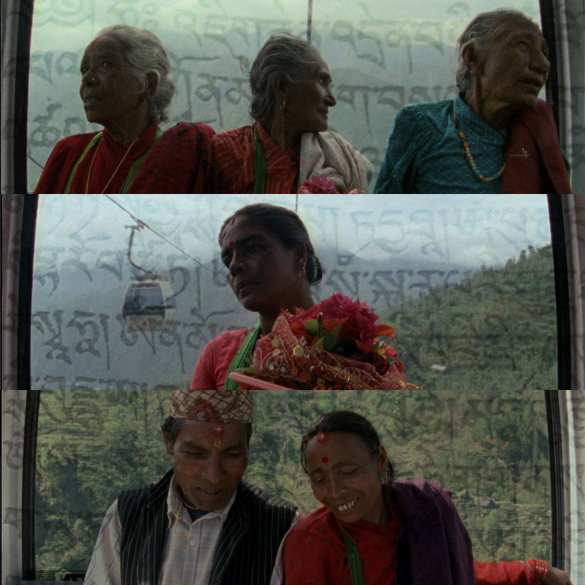

Two filmmakers, Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez directed the film using a static 16mm camera placed within a cable car. The cast consists of Nepalese locals from the surrounding region, who went through a traditional casting process. The synopsis is simple “High above a jungle in Nepal, pilgrims make an ancient journey by cable car to worship Manakamana.”[i] Manakamana is the goddess of wish fulfilment in the Hindu religion. The temple itself sits 1302 meters above sea level and overlooks the Manaslu- Himachali and Annapurna mountain ranges. Before the cable car was installed in 1998, the journey on foot would take approximately three hours; via cable car, it travels 2.8 kilometres in ten minutes. Taking away the physicality of the mountain trek, the cable car allows for a more contemplative ascension to the top of the mountain. This contemplation gives the film powerful significance as the audience observes the expressions, interactions and silence of the passengers gliding over the trees and valleys below. It becomes evident that entombed within the cable car, the passengers are, for a short moment at least, completely cut off from the world around them. They can observe, but not interact with the surrounding landscape. This for me is one of the most intriguing aspects of the film, to be absolutely immersed within one’s own humanity and alone in thought. Manakamana makes me recall an incredibly frightening cable car journey to the relatively small mountain ranges of Montes de Málaga in Southern Spain; an ascent I took alone. Within the confines of the cable car, a rare mix of claustrophobia, vertigo and impending death took over me and as I rattled up the mountain, my own sense of smallness within a large and bright world sunk in. I nervously shook my DV camcorder towards the window and filmed the journey (the results of which were edited into an experimental film entitled Communiqué). The audio track that accompanied the original footage is a monologue of whimpering, nervous internal thoughts broadcast aloud by my uncontrollable mouth and falling on the ears of no one. The journey lasted ten minutes at most and my relief at reaching the summit of the mountain was short lived as I realized I would soon have to descend at some point. The vista of the mountain was spectacular. I spent moments in wonderment of something so natural and so colossal, having grown up in vast flat land in the middle of England, any mountain, however small in comparison to others, was going to blow me away. The descent, which I had put off for a number of hours, still loomed ahead. I reluctantly placed myself within the car and gracefully swung around the carousel to return to the bustling town below. However, the experience was different on the descent. The mountain had tamed me. I rode in tranquillity and observed the barely treaded land that glided below me. Green trees and wild shrubs, untouched by human hands in decades, had flourished. As I descended back towards normal existence, the landscape below changed to busy highways and extravagant backyards with swimming pools. The sparkle of the sun on the outstretched sea ahead of me invited me back to the ground. I exited the cable car in an altered state of mind and awareness, glad to return, yet willing to take the ride again, for I understood what had transpired. The ascent was not paranoia or claustrophobia, but fear of being absolutely detached from the land, from people, and from my unspectacular life. A moment of calm and serenity was something my junk ingested brain was troubled to embrace. I was literally terrified to be alone with my thoughts. The descent was my thankful return.

Although Manakamana made a splash in 2013’s summer festival circuit, 2014 will be the film’s year of reckoning. It will no doubt play at a number of art cinemas where its affects will either be felt or ignored by the small audiences who seek it out. Early reviews of film festival screenings talked of walkouts by audience members frustrated with the lack of driving narrative.[ii] I suspect these walkouts will happen again in subsequent screenings. The film will divide opinion, for many who wish film to be puerile entertainment it will seem boring and plodding. They will be unable to engage or appreciate the artistry and simplicity of what the filmmakers have attempted to accomplish. This will be a sad misconception. For those who remain in their seats the experience of witnessing Manakamana will be immensely rewarding. If one can simply let go for a moment of the concept that a film needs to be visually evocative, that an audience needs pandering to with inane dialogue and predictable characteristics, that we need a beginning middle and end to comprehend a narrative, then Manakamana will redefine what film can achieve. When my own time finally comes, and I sit comfortably (or uncomfortably, depending on where it does screen) in my seat to watch the procession of worshippers ascend the mountain, I will recall to my own ‘spiritual’ journey in the Spanish cable car, and how petrified I was to spend a few moments without distraction, to immerse myself in my own humanity and allow myself to just breathe. Of course, it is always unwise to place something on a pedestal – when I do watch the film, a sense of disappointment could always prevail. Yet I feel that if I do not watch Manakamana with an open mind and embrace its oddity, I will have failed to experience and promote a form of cinema that I have championed in previous writings, and hold to account the cinematic disarray I have also tried to challenge.

[ii] http://www.indiewire.com/article/locarno-film-festival-review-stunning-documentary-manakamana-from-the-team-behind-leviathan-is-the-must-see-cinematic-experience-of-the-year

—

Stephen Lee Naish grew up in Leicester, UK but now lives in Ontario, Canada where he writes about film, politics and popular culture and the places where they converge. His writing has appeared in numerous journals and periodicals, including the arts and culture magazine Gadfly, the academic journal Scholardarity, and the journal of beat writing reviews and articles, Empty Mirror. His first book U.ESS.AY: Politics and Humanity in American Film is published by Zer0 Books in January 2014.