|

Complimenting an artist’s use of color has always seemed not so different from saying an unattractive person has a good personality. When you are left with just saying stuff about the palette choices, there isn’t too much else. This autumn there is an exposition on the career of French painter Jean Dubuffet at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and this thought ran through my mind until I began to think more about what I saw. After spending several hours with a man’s life’s works, I am left with the impression that his art is both sublime and at other turns, frustratingly, almost comically, lacking.

Though I have come to appreciate many artists over the years, I am always slow to evaluate art with the same confidence of film, music or literature—as if there are additional faculties I am not equipped with, and therefore if a painting doesn’t "speak" to me, then it must be my fault for not understanding what makes it a masterpiece. This is of course folly, and a moot point, as the world is comprised of non-professionals like myself, and if we think it is the Emperor’s New Clothes, then by golly, all the art collectors and dealers and critics can turn blue in the face trying to explain to us logically why we must appreciate it, but it will make no difference. Or will it? At more cynical moments I wonder if we are all victims of a P.R. blitz, much like a movie studio will decide which film it will trumpet this season, telling us how its director is a wunderkind, and hyping it to the point that we don’t realize, say, that Brothers McMullen wasnt really a particularly original or interesting film after all. It seems that it very well could have been another filmmaker or artist or musician of equal (or even significantly less) ability that could have been plucked from obscurity and crowned as the next John Cassavetes or Ernest Hemingway or Bob Dylan. To use these three men as examples, there are many people out there, fans of cinema, literature and music who wonder why others value their work at all, finding Cassavetes boring, Hemingway a mockery and Dylan’s voice unlistenable.

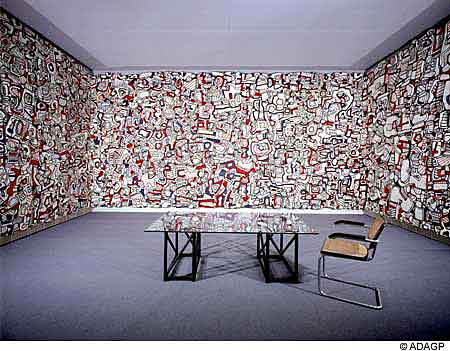

It is with these thoughts in mind that I entered the exposition of Dubuffet. What I saw suprised me. The pieces of art on a coffee table book’s page are one thing, but to walk into the next room and be greeted by 8’ x 20’ panoramas on three walls, grand pronouncements about the coming of the technological age, of the chaos of modern urban life with its overcrowding and death and hyperculture—well, it is a bit inspiring, and one must begrudgingly admit, whether or not Dubuffet was handsome, or had a good personality, his use of color was indeed amazing.

Dubuffet was born in 1901 and died in 1985. Save for the end of communism in the East and the rise of the so-called Information Age in the West, he was around for all the interesting cultural and historical goings-on the last century had to offer. He traveled the world, both further east and further west. He spoke several languages. He was quite prolific, and his art is displayed in most modern art museums in the world. My own first experience of his art—and only conscious look at an example of his work—is the sculpture outside the State of Illinois Building, that bizarre edifice of post-modern architecture that resembles a large, red and blue Millenium Falcon. This sculpture is representative of much of Dubuffet’s later work, what is most associated and identifable as his, using the same blue, white and red colors and pseudo-human forms. They are cousins to the pieces in Coucou Bazar, an elaborate collection of larger than life size carnival figures made for a theater production and I don’t like them. But his early works were of a different sort. The first pieces of the show are from 1924, and feature paintings of somber, bulbous-headed people in muted, tan-based colors. They are fascinating paintings, particularly a series of a woman, Lili, in various places in a house, appearing serene, but bored. They are complete images, of a real human form, presumably looking like Lili herself. An artist of inspiration, of promise, to be sure. Then he stopped painting.

After some time in Buenos Aires, he returned to France and joined the family business of wineselling for almost a decade. It was in 1933 that he began to pursue the arts again, but after four years, rejoined the family business to save it from bankruptcy. But later he began to paint again, and by 1942 was dedicated to it exclusively in Paris. There is a series of works depicting people on the Metro, using vibrant colors, people with varying expressions on their faces. These paintings are displayed in the second room of the exhibition, and it is fascinating to see how several children that stood impassively in the first room of the exhibit, with its somber works, are suddenly engaged in this room, being reprimanded by parents for touching the paintings. Several have approached this series, hanging low on the wall, drawn to it by the use of color and the simplicity of representation—much like their own art. I imagine these five and six year-olds thinking to themselves, "I don’t know if it’s art, but I like it."

There are paintings of dudes, boxy paintings with little spatial dimensions showing angular, basic genitalia. Looking at each of these, one begins to see faces in the trunk of Dubuffet’s nudes, the breasts as eyes, belly buttons as noses, stomach curves as jawbones and genitals as mouths. One of these "faces on the body" appears to be a comical horse, and is not so subtle.

Of the paintings during the war years, only one seems to directly portray its gloom and repression, Mur d’inscriptions (Wall of Inscriptions-1944), which is a lugubriously grey wall, words scratched into it, and a person standing on the side, baring his teeth and giving us a skull’s smile. He may or may not be in uniform. And yet smack dab in the middle of the Occupation, the middle of the war, you have vibrant colors of green and orange and purple. And why shouldn‘t there be? It seems that the sweeping generalizations we make about history, about culture in general does not stop at painting. Why should there be any consistency at all in any specific period of an artists life? Do we not over-simplify the emotional lives of everyone we do not know intimately, from movie stars to politicians, trying to pin them down, contain them, in order to make easy sense of them? An artist like the rest of us surely experiences a range of moods over a period of hours, not entire years. The paintings of the Metro Riders, each with their own messy expressions and degrees of thoughfulness and perhaps awkward happiness, makes the point. Of the paintings during the war years, only one seems to directly portray its gloom and repression, Mur d’inscriptions (Wall of Inscriptions-1944), which is a lugubriously grey wall, words scratched into it, and a person standing on the side, baring his teeth and giving us a skull’s smile. He may or may not be in uniform. And yet smack dab in the middle of the Occupation, the middle of the war, you have vibrant colors of green and orange and purple. And why shouldn‘t there be? It seems that the sweeping generalizations we make about history, about culture in general does not stop at painting. Why should there be any consistency at all in any specific period of an artists life? Do we not over-simplify the emotional lives of everyone we do not know intimately, from movie stars to politicians, trying to pin them down, contain them, in order to make easy sense of them? An artist like the rest of us surely experiences a range of moods over a period of hours, not entire years. The paintings of the Metro Riders, each with their own messy expressions and degrees of thoughfulness and perhaps awkward happiness, makes the point.

During this time, during the war, the paintings themelves became sparser, in paintings like Jazz-Band (Dirty Style Blues), done in December of 1944. Simple black figures with thin streaks of color, each man looking like the masks worn on the Mexican Day of the Dead, or at Mardi Gras as they play their intruments, which are graced with more detail than the musicians themselves.

In the 1950s he scatched into the canvas, burrowing really, in disconcerting paintings like La Metafizyx (August, 1950) and Lever du Lune aux Fantômes (March, 1951) that look like clay or copper and other metals, almost in bas-relief, with bubbles coming to the surface, suggesting, indirectly, the eponymous phantoms, creating something wholly other from what I have seen done with only oil and canvas before. And soon, that wasn’t enough for Dubuffet in his attempts at going beyond convention, because we see in the next room that he began to use other things: the wings of butterflies and sundry botanical things; it feels authentic, not like a gimmick, precisely because of the evolution from paint to trying to move beyond it. It is the most authentic form of Modern Art that I, a Modern Art Scrooge, have seen. Doing a self-portait in butterfly wings must have satisfied something primal for him, but only Dubuffet could tell us what that is.

Serenité Profuse (1957) appears, despite being oil on canvas, like a closeup of rock sediment. In Texturologie #56, painted in July of 1958, the canvas is much like Jackson Pollack’s dripwork but without the splash effect, dots of paint that taken as a whole give the impression of being sandstone ,the side of natural rock formation. With oil and water he is creating a lunar surface, stripping art literally to the elemental.

Then, his return to color, vibrant color in 20-foot long paintings, which come as a happy relief from the rocky darkness of the preceding works. An organic progression, in the 1960s, a ghoulish blur of human beings, made happy by their colors, a swirl of urban life from overhead, in such works as Echange de Vues (December, 1963).

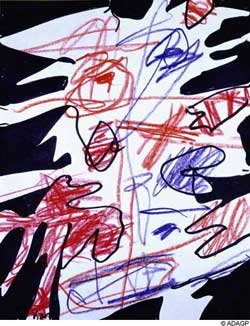

Later, in the 1970s, he began using crayons, drawing literally like a child, as if he were mocking art itself, returning to a state of simplicity of expression. Is this what he is doing ? This is where I wonder: Senile man with a Crayola, mocking our concepts of art, art commentary and appreciation, and what has value, or is he working on some level that is beyond my comprehension? Either way, it doesn’t appear to be the sort of work one does to get the attention of the world. Still, because of his reputation and adoration, it is heralded. I am reminded of Jon Lovitz as Picasso in a Saturday Night Live sketch, practically blowing his nose into a napkin or some such thing signing his name and declaring, with all his twitty (Lovitz), megalomanical (Picasso) glory, "This is worth millions, because I’m Picasso!" Later, in the 1970s, he began using crayons, drawing literally like a child, as if he were mocking art itself, returning to a state of simplicity of expression. Is this what he is doing ? This is where I wonder: Senile man with a Crayola, mocking our concepts of art, art commentary and appreciation, and what has value, or is he working on some level that is beyond my comprehension? Either way, it doesn’t appear to be the sort of work one does to get the attention of the world. Still, because of his reputation and adoration, it is heralded. I am reminded of Jon Lovitz as Picasso in a Saturday Night Live sketch, practically blowing his nose into a napkin or some such thing signing his name and declaring, with all his twitty (Lovitz), megalomanical (Picasso) glory, "This is worth millions, because I’m Picasso!"

Just like Picasso and Jackson Pollack own oeuvres, these later paintings are not like Dubuffet’s early work. He has nothing left to prove. We already know he can do a likeness of a person, paint in realism—that he has passed the test as it were, so he can move on to other things. What makes someone like Dave Eggers, with his book A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius so interesting isn’t that he is naive, but specifically because has read All The Right Books, he does know The Rules, The Protocols and Fifty-Cent Words—then deliberately chooses to ignore them and create his work the way it must be created. Perhaps we would not find so impressive the same book written by someone who had never read a book before. An artist can color outside the lines, as long as he knows that we know that he’s talented enough to stay inside them if he wanted to.

In Dubuffet’s self-portrait from his later years, that which is used for the two-story poster advertisement on the Pompidou’s exterior, there are red stripes in his left ear, blue stripes in his right ear, a different number of them in different proximity. This is true of the forehead, the eyes, the nose, the mouth. He is hideous, really, like a skinless head with muscles exposed, patched together, a child’s playfully horrific conception of Frankenstein’s creature—all dressed up in the three colors of the nation’s flag. What do these lines signify? Is there meaning in the number of lines, of red here or blue there ? Is it arbitrary or is there method in the method? It is this motif that is most prominent in the last decade of his work. I may be showing how wet behind the ears I really am by repeating to myself the four words that many have said as they stare up at a painting with both envy and contempt: I Could Do That. But really, could I? Is it as simple as it looks? Or is it more about the work at large, the journey to get to that point, of boiling representation down to its essence? Art is conjuring, the artist is the conjurer.

What we are left with is a sense of mania. Almost like the repetition of colors and images—indeed nearly identical paintings—is an attempt to get it right, to nail it, to make it true. Is it indulgent? Did he care? Does it really matter? How much does one’s art change when he or she is the toast of the world? Is he painting for the accolades at that point, or, having received so much already, is it just for himself? They say he thought art should be artless; that he disowned his early work; that he deliberately turned away from the masters; that he based one of his most well-known series on some doodles he did while on the telephone. Doodling is mostly an unselfconscious act, hardly an affectation. And authenticity in one’s work is the first thing that the artist, and the audience, is asking for.

|