|

On Monday night, October 15th, the Oakland Athletics and the New York Yankees played the decisive game of their divisional playoff, the finale of one of the most exciting and well-played contests in years. That same night the Dallas Cowboys and the Washington Redskins put on a display of Monday Night futility the likes of which is rarely seen, in a game that had no import beyond determining which of the two teams is the worst in the NFL. The ratings released the next day revealed that the latter outdrew the former to the tune of some two million viewers. On Monday night, October 15th, the Oakland Athletics and the New York Yankees played the decisive game of their divisional playoff, the finale of one of the most exciting and well-played contests in years. That same night the Dallas Cowboys and the Washington Redskins put on a display of Monday Night futility the likes of which is rarely seen, in a game that had no import beyond determining which of the two teams is the worst in the NFL. The ratings released the next day revealed that the latter outdrew the former to the tune of some two million viewers.

Basketball has flash, hockey has grit, but for the foreseeable future football and baseball are the two forms of gladiatorial escape that excite the most fervent American passion. Between them they cover all but roughly two months of the year. They overlap only briefly, with baseball reaching its zenith as football is just starting to become interesting. When the two do go head to head football invariably wins, despite the gap in seasonal importance. This phenomenon raises a question, the implications of which extend beyond just the collective passion for sport: what has happened to baseball?

Organized sport in America, as in all cultures for all time, serves a function. Age-old verities of loyalty, aggression, victory, and defeat are reaffirmed each time players take the field, and the ever-expanding economy of sport suggests that the process is as important now as it has ever been. But each sport plays with the values in a different way. In the differences between baseball and football, and in the numbers associated with cultural allegiance to the two, a different kind of American history is written, one that shows where we have been and subtly suggests where we might be headed.

The two games could not be more different. Perhaps this is stating the obvious, but it is nonetheless the heart of the matter. The most common way to watch the games is on television, and the knock on baseball is that it is a boring game. In football the action is nearly constant, with barely enough time between plays for the broadcasters to show a replay (perhaps more on especially significant occasions) and offer breathless apoplexy about what has happened and what is likely to happen next. Football commentary is so unnecessary that John Madden, a mostly senile ex-everything, is one of the game’s most respected analysts, and Monday Night Football has been forced to turn to Dennis Miller to make its analysis interesting. It would be a mistake to not acknowledge that both of these men are highly entertaining (for wildly different reasons), as is the game itself. There is something riveting about it: the endless repetition of soft violence, the excitement of the big play, the sheer weariness of it when all is said and done. Yet among the many things that football is there is one thing that it is not, and that is contemplative.

The exercise of watching a football game is not one that invites serious thought. Football is catharsis and cleansing, the satisfaction of playing hard and bearing scars as red badges of victory. Without it there would be a giant void to fill. Furthermore, the regularity of the football schedule and the amazingly small number of contests (16) in a season allow for a very concentrated and regimented experience that not only satisfies but goes down easy. What else do you have to do on a cold Sunday afternoon?

Where football welcomes the spectator baseball is far more standoffish. The release afforded by watching baseball is something one has to earn, and it is a much different feeling altogether. In baseball the contest is seldom limited to one game—teams can play twelve times or more a year, with tension and significance building along the way. The pace is slow, the action crests and rolls. Often, nothing happens. This is a good thing, and that fact has been forgotten.

As has been remarked, baseball is one of the only endeavors in which consistently succeeding 30 percent of the time is an almost sure ticket to the Hall of Fame. Baseball is neither played nor watched for the satisfaction of the big play. The big plays that happen in baseball (and they do happen) are only the largest of the small parts, each of which is essential to the whole. There are 162 games in a baseball season, and the playoff rounds consist of five, seven, and seven games. It is unique among team sports in that there is no clock—play lasts until the matter is settled. At any given time during a single game there may not be any action on the surface, but just beneath it a hundred things are happening at once.

Consider the following (entirely hypothetical) scenario: there are three weeks to go in the season, and the Orioles are at home playing the Red Sox. The two teams will not play each other again this season until the final week, the last series of the year before the playoffs begin. The Red Sox are in first place, the Orioles in second. The Sox have lost the first two games of the three-game series, allowing the Orioles to gain two in the standings and cut the overall deficit to one. Should the Orioles win today they move into a tie for first. The remainder of the Red Sox schedule is cake: a trip to Minnesota and Kansas City, then home against the Devil Rays and the Angels. Their only remaining tough games are to conclude the season against the Yankees and the Orioles again. By contrast the Orioles have to play the Yankees twice, as well as the Athletics and the Indians. For them only the Devil Rays represent a real break. If the Orioles lose today they drop two games back with a tough road to go. While not in a must-win situation, the Orioles need this game.

The score is Red Sox 4, Orioles 2 in the home-half of the sixth inning. The Orioles are sending their five, six, and seven hitters to the plate—not quite the heart of the order, but solid hitters capable of doing damage. The Red Sox starter is up to 86 pitches, a count high enough to start considering the bullpen given his history of elbow trouble. He throws right, and of the three Orioles hitters assured a trip to the plate the latter two are lefties. The hitter scheduled fourth also hits lefty. The Red Sox have reliable relievers from both sides warming up to ensure readiness for every possible scenario.

The first hitter singles to right field. He has only average speed, but has to be considered a threat to steal in a close game. The second and third batters strike out. Due to some fine defensive batting the pitch count is now up to 105, and the Boston manager has his left-handed reliever ready to go. But the starter has good career numbers against the next hitter—the guy is seven-for-thirty two lifetime, a .218 average. He has been on a hot streak... still, the manager elects to stick with his horse. On the fourth pitch the man on first steals, a risky move to be sure, but one that pays off. He’s now in position to score on a single.

Boston is up two runs, and can barely afford to let the Orioles slice into that lead. The count is now two balls, two strikes. The hitter is looking fastball, and looking to hit it to the opposite field. The pitcher has two options: try to overpower him anyway with inside heat or try to fool him with off-speed stuff, maybe a change-up or curve. He’s already seen the fastball twice, and the curve has been hanging all day.

What happens next? The hitter could ground out, fly out, or strike out and the inning is over. He could foul the pitch off or take a ball and start the whole process again, this time with one more variable. He could single and score the run to cut the lead and keep the inning alive. He could double and not only prolong the inning but also end up in scoring position. He could hit a home run and tie the game, changing the complexion completely. What happens next is anybody’s guess, in other words, but it is only going to be half the story. On every pitch, at every moment, the vast tides of the game are at work and seemingly insignificant choices and events can have a major effect on the game, the series, the season.

It’s likely that the average baseball fan (and even the above-average baseball fan) does not consider every single variable on every single pitch. But it’s all there, just under the surface, all the time.

The game of baseball has changed very little over the hundred years or so it’s been around, and there was a time when the very same minutia that now goes ignored was a source of deep and abiding cultural passion. Far from being considered boring, baseball was followed in such detail that vast masses of emotion were swayed with every game. Men like Roger Maris, Mickey Mantle, Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, Satchel Paige, and literally hundreds of others were national icons—models of strength, endurance, class, or some combination of these. To be a national icon now one has to hit 73 home runs and even then share a stage with mediocre journeyman quarterbacks. Cal Ripken was baseball’s last national icon, and there is no heir apparent to his throne. The game of baseball has changed very little over the hundred years or so it’s been around, and there was a time when the very same minutia that now goes ignored was a source of deep and abiding cultural passion. Far from being considered boring, baseball was followed in such detail that vast masses of emotion were swayed with every game. Men like Roger Maris, Mickey Mantle, Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, Satchel Paige, and literally hundreds of others were national icons—models of strength, endurance, class, or some combination of these. To be a national icon now one has to hit 73 home runs and even then share a stage with mediocre journeyman quarterbacks. Cal Ripken was baseball’s last national icon, and there is no heir apparent to his throne.

In answering the question of what has happened to baseball, and why, one begins to see a way in which the culture has fundamentally changed. There is no longer a national passion for detail and nuance. It has been replaced, likely permanently, by a passion for quick release and visceral heroism. There is a reason that Saving Private Ryan was so much more well received than The Thin Red Line.

Is any of this overstating the case? Maybe, but probably not. Trends in art, music, or film are highly representative of the culture, but none of these tends to excite the same general passion as sport. No other aspect of the popular culture stretches so far, and what we watch says a great deal about who we are. It seems that in the current climate there is no patience for baseball.

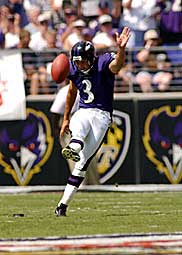

There are those who would see something like DiMaggio’s record 56 game hitting streak, and the fact that the record is not likely to ever be broken, and use this to bolster their argument that nothing happens in baseball. These people will find their solace in the amazing fact that, for 34 straight games and counting, Baltimore Raven Matt Stover has kicked a field goal.

|