|

On Friday, August 8, 1969, John, Ringo, Paul and George walked across the street for a photo that was to become the cover of their Abbey Road album. As many know, this was the Beatles' last recorded album, though it was released before their swan song, Let it Be. Given the album’s content, it has a sense of closure—to use the parlance of our times. After all, the final song on Abbey Road is "The End." Thus, the album is a fitting end to the band; and its cover, with the four of them exiting stage left, a fitting final image.

What is it about Abbey Road’s cover that speaks to us ? I would say it’s a combination of its simplicity, its sybolism and even a bit of present nostalgia. It is hardly a serious photograph; the manner with which the Beatles parade across a street, the space between them, reminding us of the wacky fun they had in the films A Hard Days Night and Help, has a certain smirk to it, as if they’re trying not to look at the camera or they will laugh. Plus the sight of the ‘‘Fab Four’’ all in the same frame together (on speaking terms or not) and the fact that they are outdoors on a deserted but inconspicuous London street, adds up to a certain sense of, well, relative normalcy for a group of guys with their stature. Even this timelessness is alluded to in the length of Abbey Road itself, paved to the horizon, infinite.

It is this image that attracts countless Beatle fans to get off the London Underground at the St. John’s Wood Station and take the five minute walk up to Abbey Road Studios, in the middle of an otherwise quiet, middle class residential neighborhood. There is a synagogue nearby, and the residences along that stretch of Abbey Road are townhouses, apartments and condos. It is mild mannered, an odd stretch of street for such a monumental recording studio and a celebrated pop cultural landmark—like the real restaurant in Upper Manhattan that doubles as the coffeeshop on Seinfeld and the steps of the Philadelphia Library that Stallone heroically ascends in Rocky II (and V). Like these other examples, Abbey Road is an otherwise commonplace location that we would otherwise pass without thought if we didn’t watch television or go to movies or listen to music. They are places plucked from the quotidian and placed, due to the power of celebrity and pop culture, and put on the map—even if we do feel a bit foolish taking our picture there.

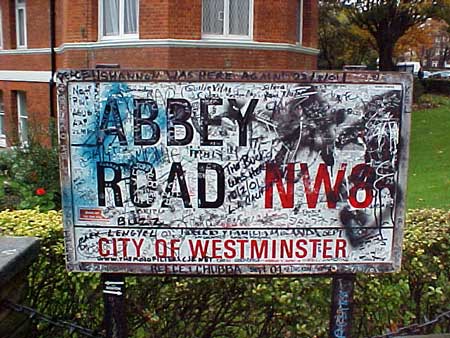

I stood on the street on an overcast Sunday, November 18th, exactly thirty-two years, one month and nine days after the photograph was taken. The buildings are the same ; it is only the cars, and the number of them, that have changed. And, of course, the attendant mythology; the street signs and cement fences around Abbey Road Studios are filled with the scrawl of worshipful graffiti, much like Jim Morrison’s grave on the other side of the English channel.

Much of this scrawl is ridiculous. Rather than being heartfelt expressions of private yearning and dedications to the band, it is, even more than Morrison’s grave, self-conscious preening, the graffiti equivalent of people in a crowd waving and making funny faces at the TV camera. The messages are overdone, either a false sense of dedication or an almost tongue-in-cheek adulation. Some are about the Beatles, others unrelated. Some basic poetry about the genius of the albums or anguish at the death of John Lennon, trivialized by the sort of lyrical content that the Beatles transcended to become who they were. Sure, some of it is wonderful, poignant and funny, but the majority is a parody of graffiti; really, people writing what they think they should be writing out here, the clichés that are expected of them. Perhaps this is a bit harsh; the real impact is in the doodles and scrawls taken as a whole—not the individual words, but the collective. A simple message, in fact—these guys made songs that we really liked, and we come here to express it.

Adding to the mystique of the photo is its contribution to the ‘‘Paul is Dead’’ conspiracy theory, which was at full throttle in 1969. The website www.rareexception.com discusses how Abbey Road’s cover art fit into the puzzle :

The clues are obvious. The cover shows the Beatles walking across Abbey Road. John is dressed in white, as the preacher. Ringo is dressed as pallbearer, Paul, who is out of step, barefoot, and the only one holding a cigarette in his right hand when he is a left hander, is obviously a corpse. It is rumored, although we aren't sure, that people are buried barefoot in England ... George is dressed like the grave digger. A Volkswagen has a license plate that says "28 IF" followed by "LMW." At the time of the release of the album, Paul would have been 28 if he were alive (counting 9-month pregnancy) and hmm... Linda McCartney Weeps? See the hearse in the background ?

Of course this is a bit of a reach, as all of that was hooey. Or was it ? It has emerged in more recent years that the band and their handlers were very much aware of the rumors and crackpot theories and, at the very least, did not go out of their way to squelch them once they proved to be a good marketing tool. Regardless of how cynically or not one wants to look at it, the bottom line is that icons like the Beatles know and understand the power they wield (bigger than Jesus, Lennon famously lamented) and how, with the click of a camera, an idyllic north London stretch of street—recording studio there or not—can be turned into a tourist mecca that will cause traffic jams and headaches to locals for decades to come. Years later, in the ‘90s, McCartney would release the album Paul Is Live, with a cover parodying Abbey Road. This time, McCartney is tugging on the leash of his sheepdog, and the white Volkswagen licence plate is 51 IS, telling us that he "IS" alive and 51 years old and obviously still doesn’t know the answer to the question, ‘‘Is nothing sacred?’’

So horns are honking because a family of tourists are blocking traffic to get that photo. They’re taking the photo from the opposite side of the street, the incorrect way. I want to help them, to make their photo a true mimic of the album cover. If you’re going to come all the way here, after all, it should be accurate. They have a little girl with them, the ‘‘Lennon’’ in terms of placement in the photo who will no doubt appreciate this photo in years to come. The horns still honk, which doesn’t diminish the smile on the faces of this family nor the others that come in succession to take the photo. Some in the cars wait patiently, indulging the pedestrians; others do not. They tap at the horn, not excessively, but seemingly to say, ‘‘Yeah, yeah, it’s Abbey Road, but I don’t have all day to wait. Get your picture and go.’’ Still, when a London driver passes this street, in front of the studio, he has to know what to expect. And I suspect, not so deep down, it is really a faux-exaspiration some of these drivers have; the fact is they know it’s Abbey Road, they are proud, and more than a few get a thrill each time they pass it.

The tourists continue to take the photos, complicated by the traffic moving in the opposite direction than they are accustomed to. But like spies on a recon mission, they dart out into the street, snap the picture and run back, giddy at having captured this piece of something. Just another day in the life.

Not eveyone here is drawn for the same reason. Laure Feton, a 26-year-old Parisian, looks forward to returning to France and showing her father the picture of herself at Abbey Road. ‘‘It is something even more important to him, something that had a large impact when he was around my age,’’ says Feton. ‘‘Being here and seeing the place where the photo was taken, where the album was recorded, it is something that will make my dad smile.’’ For Feton, it is a connection between generations, harkening back, one can guess, to the first time the father played the record for the child. For me, Abbey Road came later. The first was Help! and, to this day, next to my father’s name in marker on the cover, written when he was 18 years old, there is my 6-year-old attempt at penmanship, big blue Crayola letters declaring that it belonged to me now.

Still, there is something quixotic about visiting places like Abbey Road and having them mean something to us. There is a silliness as we negotiate ourselves around the area, aware of the others, like scavengers, but not talking to them. We want to be the only ones; we want it to retain its seriousness. We want our cultural landmarks and texts to remain ours individually, or at least be experienced on our terms. We want to believe that, when we get to the Leaning Tower of Pisa, we will be the only ones there, without the tourist trap shops just out of camera range. We want the postcard experience without the postcard, but we cannot have it with the Leaning Tower or Abbey Road. That which makes it a destination of worth is that which does so for everyone.

I once visited the apartment where Philip Roth lived in Rome in 1960, and it did not have dozens of people taking pictures, group tours or even a plaque. It was mine to have for a moment as I stared up at the apartment, thinking about the story ideas that must have been percolating in Roth’s head before he left Rome for a position at the University of Iowa’s famed Writers’ Workshop; before he could have known what a force in contemporary fiction he would be.

And here, at Abbey Road in London, where the Beatles already had a secure place in the cultural pantheon, I take my turn on the crosswalk. It may be silly, foolish or trivial in the face of so much else. But for a moment, it is my experience, and mine alone. Which is what makes us fans in the first place.

|