|

So he knew that all this was but a confusion

of dreams and an illusion of Hashish and he

was vexed and said to him who had roused him,

"Would thou hadst waited till I had put it in!"

"The Hashish Eater’s Tale," The 1001 Nights

The desire to be alone is as incomprehensible to the Afghan as it is to most people in the East. On buses, Turkish soldiers lean on you and fall asleep like babies. Iranian fellaheen put their arms around and tell you dirty jokes that you don’t understand. The wish to separate oneself from others, to pull away (a natural reflex among Europeans) is considered not just rude but actually pathological, a form of mild insanity. When the love-sick Madjnun goes off to the wilderness by himself in the Arab folktale Layla and Madjnun, it’s a clear indication the boy’s gone over the edge. His name, Madjnun, means "Madman," the barking-mad one who has abandoned his clan to live among the wild beasts.

Madness in the Middle Ages was associated with the sea. They put mad people in boats and sent them off to the deep—like to like. Remoteness, isolation and insanity are linked in both the feudal and the tribal mind—the two kinds of societies I often fantasized belonging to, but knowing me I would probably have ended up on that ship of fools.

My fascination with the practices of communal societies does not extend to actual groups of people, especially those of my own tribe: hippie backpackers. I try again to find a little quieter room. I address my concerns to Mr. Zindabanan.

"Was there something lacking in the accommodation, Mr. Dalton?" he wants to know.

"Well, no, but you see, I was thinking more of a room to myself, bâstân, do you understand? Private, a private room."

"You are sick?"

My desire to be in a room by myself—may the Prophet translate the foolish wishes of the infidel—is too bizarre a concept for Mr. Zindbabanan. The most I can get across to him is that "the dorms, lovely as they are, are too noisy, crowded. I need somewhere quiet, do you see? To, uh, meditate."

"You are religious man?" He seems surprised.

"Well, in the cosmic sense I suppose…. I don’t know that I see God as a religious entity as such but…."

"Fer Chrissakes," says Barry, "you’re not going to get into a theological discussion over a hotel room, are you?"

"No private room," says Mr. Zindbabanan, putting an end to our nice theological chat. "But I put you in with two nice Italian boy."

We are shown the room. Two skinny, giggling guys. They snigger, they giddily karaoke along to San Remo bubblegum on a tinny cassette player, the hajjis of yeh-yeh, bopping to Europop all night long. Ah, Italian speed freaks—just what we were looking for.

"Listen," I say to Barry, "I’d advise you to take your traveler’s checks and hide them in ten different places because if you don’t these guys are going to steal all of them."

"They seem perfectly harmless to me. Nice boys."

Barry takes the opportunity to practice his phrase-book Italian on i ragazzi: "I do not smoke much. Neither does my cousin. We have no occasion for our umbrellas. The station clock has a different time from my watch. I haven’t any postage stamps and must write to my aunt."

It’s a little-known play by Ionesco, and after a few puffs on the hubbly-bubbly thoughtfully supplied by the hotel I get into it. And to think I suspected those nice boys of larceny. The beds are made of rough-hewn wooden poles with crudely carved finial posts at the four corners and with hemp strung across the frame. The mattress is a thin pallet of straw covered with rough cotton. It looks wonderfully archaic, a bed straight out of one of my childhood books— Everyday Things in Ancient Greece, something Odysseus might have slept on—and is remarkably comfortable. I sleep on my backpack but nevertheless in the morning those nice boys, I ragazzi, have gotten to several of my hiding places. And all of Barry’s. I split what money I have left with him.

Tribal family in a tent outside Herat

© David Atkinson

|

We head out to see the poppy fields now in bloom that stretch out to infinity. A field of opium poppies is a sort of intoxication in and of itself, blood-red petals against the saturated green leaves and stalks, nodding their heads this way and that, waving like turbaned Caliphs rising up out of the ground "from where some buried Caesar bled" and trembling in out-of-phase flashes of brilliant hallucinatory color.

"Look at that," I say, "Isn’t this the most fantastic thing you’ve ever seen?"

"But you’ll never get something like that on film," replies Barry, always the consummate professional. I decide to humor him.

"Why not?"

"It’ll look like a bad roto-gravure. Your eye can see far more apertures than a camera, almost twice as many F-stops, so to speak, f-stops being the ratio between the focal length and the aperture." What is he on, anyway?

"Really?" I reply. "I always thought the camera captures things the eye couldn’t."

"The eye can see a far greater dynamic range than can film, far more, given the UV and IR ends of the spectrum that film is insensitive to. F-stops are the ratio of the diameter of the aperture to the focal length of the lens…." Barry is off and running; there’s no stopping him now.

It’s not that I am impatient with his explanation—optics having been a subject of intense study for me since childhood—but my mind is wandering.

The poppies, of course, have even less interest than I in these abstruse matters. If it could talk—and plants, believe me, do speak to you in the most direct manner possible—the poppy would have nothing but disdain for the clumsy apparatus of the camera, that mechanical purveyor of thin substitutes for reality. The poppy has its own occult photography, opium, a snapshot of the plant’s soul. The poppy does not trifle with visual replicas, it deals in the f-stops of the mind. The dreaming plant, the emanation of the poppy that talks to the mind with the mind itself. A potent little vegetable god who with his own shamanistic chemolingo hypnotizes its subject, shape-shifts, and for a drowsy hour or two you are the poppy.

You see, in some mysterious way its image, like an eikon of a dumb divinity, is reflected in receptor sites in the brain itself. An uncanny mental mirror created by the brain independently of the image it would eventually reflect—as if the negative preceded the taking of the picture. It is an incubus that haunts the brain with its narcotic ghost, a transubstantiation of plant spirit that physically replicates its essence in the mind—a camera obscura that develops negatives into dreams and turns its host into a phantom of itself.

Barry’s dissertation brings me back to reality—if that’s the word:

"….thus the curious affair of the smaller number being a wider aperture, i.e., a 50mm lens with a 25mm aperture is F2, but a 50mm lens with a 2mm aperture is F25. Typically, each ‘stop’ on a lens (clickstop) is a halving or doubling of the amount of light that is allowed to enter the lens—"

"Hmmm, I see the problem. But why not just take a fucking picture anyway?"

Days pass and Barry’s mood does not improve. One thing or another—what a prat!—prevents him from practicing his melancholy art. For some odd reason photography induces an anxious and gloomy mood in its practitioners, every image a kind of funeral, the craft itself, with its embalming fluids and Stygian darkrooms is akin to that of the Egyptian mummifier—and with a similar intent—the preservation of life in a suspended form.

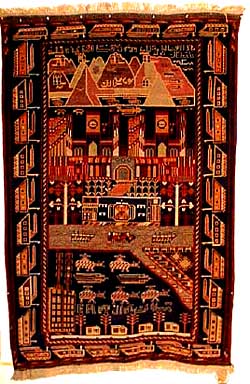

Carpet depicting City of Herat at time of Soviet invasion

|

Ah, I know just the thing to raise Barry’s spirits, a little visit out to the "jolly, clean Afghan girls." Not that this was Barry’s cup of tea exactly, but for some reason he was obsessed with photographing whores and whorehouses. He’d dragged me to whorehouses all over Turkey to fulfill his perverse hobby (with me always having to pose as the horny john).

The clean, jolly Afghan girls lived in a white tent outside the city walls, and, unlike the respectable women in Heart who only wore black from head-to-foot in the burqa, the whores wore only white.

They are friendly, chubby, and made up like Tammy Faye Baker. They were drinking Polish vodka, smoking, flipping through Iranian movie magazines and tattooing themselves with henna. Loud Bombay movie music is playing on a boom box. When they see us enter they slip a Europop tape in the player. After a few cups of chai, shots of Ukrainian scotch and much giggling, the older woman comes abruptly to the point:

"Fuck with rubber, four dollar."

"Yes, well that seems perfectly reasonable," I say, "but, actually no. You see we’ve come here…."

"You no like? You like boy, maybe?"

"Now wait a minute, I may be English but…. no, it’s my friend Barry here. He wishes to photograph. Sâxtan vâz. Make photo. Understand? Barry, go on, show them your camera."

When they see the Nikon, a look of horror comes over them. They hide their faces as if about to be smitten by the Lord of Hosts. "No photo! You go!" And with that they push us out of the tent without ceremony. Well, who would have guessed that taking their picture was a more grievous sin than their other line of work?

Barry’s not-very-original theory is that they don’t want us stealing their souls.

"Well, no" I demur, "that seems highly improbable. I mean, c’mon, they’re not Trobriand Islanders, fer chrissakes. They’re drinking vodka, smoking like chimneys, playing Abba, and trying to sell us Soviet handguns. They’re Herati whores, big city girls."

"You might be right."

"Still, I think we spooked ‘em somehow."

"You mean I spooked ‘em."

"Yeah, that’s what I mean, Barry. Stop being so fucking pathetic all the time. Who the hell knows what it was? It’s probably something far more banal, I should think. The business with the camera—perhaps they thought we’d get them into trouble with the police. And let’s face it, our not wanting to fuck them was a bit suspicious, don’t you think?"

"You could have made the effort."

"I am no longer going to be a human sacrifice in the fleshpots of Asia," I say. My words, resounding in the cavernous souk, sound like Lord Kitchener at Khartoum.

Actually I probably did think Barry had spooked them. Barry was a jinx of sorts, a useful friend to have in the land of the djinns, given the clashing rocks of the Symplegades that crush travelers in their phantom jaws. It was as if Barry’s paranoia were a physical quantity that, having achieved critical mass, in some occult way absorbed my own and siphoned it off. Maybe Jonah wasn’t a jinx—or perhaps this is what they called paranoia in the bronze age—and perhaps it was Jonah’s paranoia (about that unfinished business in Nineveh) that caused him to get thrown overboard.

Men drawing water from the well at the Friday Mosque.

© Ric Ergenbright/Corbis

|

Following our rout from the tent of the whores, we go to the other extreme. After ritually washing our hands, face, and feet in the stone fountain provided, we enter the sublime Friday mosque. The mosque had been recently reopened to foreigners. It had been closed for years to infidels who had defiled the holy site: Brigitte Bardot had danced there naked by artificial moonlight—a transcendental moment for English schoolboys, but apparently not for the Muslim devout. (What was that movie, anyway?) A huge open courtyard the size of a football field surrounded by colonnades and alcoves decorated with brilliant tiles. The sanctuary a great empty quadrangle, fit for an army of angels to descend, or for houris to recite the mystic quatrains of Rumi while Sufis whirl themselves into an ecstatic state.

But all the shimmering faience of the Tim–rid dynasty is not enough to relieve Barry of his gloom. Barry superciliously dismisses the mosque as unsuitable to his sullen craft. “Postcard stuff,” he sniffs. After days of bitching about this and that, I’d had enough of his whining.

"What is it? What? We’re here in paradise and you’re still whining. What is your problem?"

"Perhaps it’s me," he says dolefully.

"Oh, no, it couldn’t be that. Stop being so negative. Just take some pictures and you’ll feel better."

"Of what?"

"What are you talking about? You can point your camera in any direction and have amazing shots. Jesus, a blind man could take great pictures here."

"That’s just my point. It’s all so picturesque, it’s a goddamn National Geographic assignment!"

"Well, what do you want to do?"

"I dunno."

"Maybe we should consult the soothsayer."

We are directed to the house of a wrinkled old man who crouches on a kilim in an otherwise empty room. He uncannily resembles my landlord in New York. Perhaps this is what Mr. Finkelstein does on his vacations. I will always think of him as spending his holidays casting fortunes in a little room in Herat.

Much consulting of omens and various forms of divination and mutterings: sleep ... journey ... wind scatter the seeds of the poppy ... the hare must return to its lair. Wonderful stuff! He has a contraption that consists of disks of painted leather that can be rotated—the so-called cosmic compass. It’s based on a zodiac laid out in a circle, and, like a color wheel, it encloses a number of other circles with phases of the moon, the elements, animals, and bizarre-looking spiritual beings on them. Each of these images is associated with a letter that has a numerical value and these in turn relate to the nature of the question. It seems like a complicated wheels-within-wheels Ptolemaic system, but since almost any question you bring to an oracle generally boils down to, "Will what I’m thinking of doing succeed?" the cosmic compass, like all divination, rests on a simple yes-or-no response.

Barry’s question, in any case, is a simple one. Should he stay or should he go?

"Your house call to you," the old man says. More of a head-shrinker than a diviner of the Unknown, he just reads the vibe, which is probably what the Pythonness did at Delphi. And, let’s face it, Barry’s mind wasn’t that hard to read.

I hated to leave Afghanistan—I’d only just arrived in the land of The Thousand and One Nights—but the thought of Barry trying to get back to "civilization" alone was a bit alarming, so said I’d go back with him. The problem was that the minibus back to Iran left at 4:30 in the morning and after a few pipefuls of hashish one slept the sleep of the blest.

|

By and by I came to a Hammam and entering looked about me I found it clean and empty. So I sat down by the fountain-basin, and ceased not pouring water on my head, till I was tired. Then I went out to the room in which was the cistern of cold water; and seeing no one there, I found a quiet corner and taking out a piece of Hashish, swallowed it. Presently the fumes mounted to my brain and I rolled over on to the marble floor. Then the Hashish made me fancy that a great lord was shampooing me, and that two slaves stood at my head, one bearing a bowl and the other washing gear and all the requisites of the Hammam. When I saw this, I said in myself, "Meseemeth these here be mistaken in me; or else they are of the company of us Hashish-eaters." Then I stretched out my legs and I imagined that the bathman said to me, "O my master, the time of thy going up to the Palace draweth near and it is today thy turn of service." At this I laughed and said to myself, "As Allah willeth, O Hashish!" Then I sat and said nothing.... They brought me into a cabinet, wherein they set incense and perfumes a-burning. I found the place full of various kinds of fruits and sweet-scented flowers, and they sliced me a water-melon and seated me on a stool of ebony, and said, "O our lord, Sir Wazir, health to thee for ever!" Then they went out and shut the door on me; and in the vanity of phantasy I arose and removed the waist-cloth from my middle, and laughed till I well nigh fainted. I gave not over laughing for some time and last quoth to myself, "What aileth them to address me as if I were a Caliph and style me Master, and Sir? Haply they are now blundering; but after an hour they will know me and say ‘This fellow is a beggar’; and take their fill of cuffing me on the neck." Presently, feeling hot I opened the door to the outer hall, which I found hung and spread with magnificent furniture, such as it beseemeth none but kings; and the pages hastened up to me and seated me on the divan. Then they fell to kneading me till sleep overcame me; and I dreamt that I had a girl in my arms. So I kissed her and set her between my thighs; then, sitting to her as a man sitteth to a woman, I took yard in hand and drew her towards me and weighed down upon her, when lo! I heard one saying to me, "Awake, thou ne’er-do-well! The noon hour has come and thou art still asleep."*

I woke up. Barry had gone.

*Adapted (basically a pronoun shift) from "The Tale of the Hashish Eater" in the Alf Laylah wa Layla: The Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night translated by Richard F. Burton

Check back in two weeks for Part IV of "An Infidel in Afghanistan."

|