|

In May 2001, Ruben Patterson, a professional basketball player for the Seattle Supersonics, was convicted of attempted rape after he forced his children's nanny to perform a sex act on him. Patterson's punishment for this offense was a suspended sentence consisting of 15 days of house arrest—presumably without a nanny to assist him with parental duties, as well as a five-game suspension by the National Basketball Association.

"I'm not no rapist," a beaming Patterson eloquently explained to the media, assembled in August 2001 to witness his signing of a $33.8 million contract with the Portland Trail Blazers. "I'm a great guy."

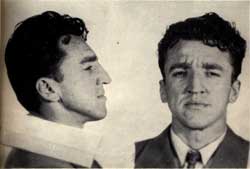

In June 1948, a 27-year-old drifter and petty criminal named Caryl Chessman was sentenced in California on two separate counts of what was essentially the same crime to which Ruben Patterson pled guilty. Caryl Chessman's punishment: two death sentences. In June 1948, a 27-year-old drifter and petty criminal named Caryl Chessman was sentenced in California on two separate counts of what was essentially the same crime to which Ruben Patterson pled guilty. Caryl Chessman's punishment: two death sentences.

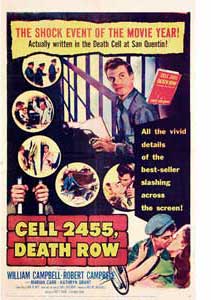

In the twelve intervening years between his sentencing and execution, Chessman lived and tirelessly labored in Cell 2455 on Death Row in San Quentin Prison, shaping what has to be one of the most remarkable bodies of work in American legal history: three wide-selling memoirs—Cell 2455 Death Row (1954), Trial by Ordeal (1955), The Face of Justice (1957)—and one novel—The Kid Was A Killer (1960), numerous articles and an unrivaled expertise in American law.

"With extraordinary energy, Chessman made, on the very edge of extinction, one of those startling efforts of personal rehabilitation, salvation of the self," wrote Elizabeth Hardwick in a poignant essay that ran in Partisan Review at the time of Chessman's trip to the gas chamber. "It was this energy that brought him out of darkness to the notice of the Pope, Albert Schweitzer, Mauriac, Dean Pike, Marlon Brando, Steve Allen, and rioting students in Lisbon (Lisbon!)."

Chessman's case became a staple of Lenny Bruce's stage routine; even the conservative William F. Buckley, Jr. was moved to defend him; Chessman's Cell 2455 Death Row was adapted into a 1955 feature film (the autobiographical content altered by Hollywood so that Chessman became someone called "Whit," but the particulars remained the same); his books were translated into several languages; journalists from South America and Europe regularly came to interview him; and popular songs, like Ronnie Hawkins' "The Ballad of Caryl Chessman (Let Him Live, Let Him Live)," were released to help ward off the death that would, despite eight separate stays of execution and countless legal delays, inevitably claim him. Chessman's case became a staple of Lenny Bruce's stage routine; even the conservative William F. Buckley, Jr. was moved to defend him; Chessman's Cell 2455 Death Row was adapted into a 1955 feature film (the autobiographical content altered by Hollywood so that Chessman became someone called "Whit," but the particulars remained the same); his books were translated into several languages; journalists from South America and Europe regularly came to interview him; and popular songs, like Ronnie Hawkins' "The Ballad of Caryl Chessman (Let Him Live, Let Him Live)," were released to help ward off the death that would, despite eight separate stays of execution and countless legal delays, inevitably claim him.

And yet, in the perennial battle to abolish capital punishment—recently rekindled by the departure of Tim McVeigh and the arrival at the White House of a man who, as governor of Texas, presided over a nearly unfathomable 153 executions—one seldom, if ever, hears the name Caryl Chessman.

This amnesia about Chessman is, in itself, a remarkable story. At one time, not so long ago, Caryl Chessman was a household name, a pinprick at the collective conscience of America. He has, however, been effectively expunged from American history. Short summations of his case can be found buried deep in a few thick tomes about American jurisprudence, and passing references are made in social histories of the 1950s. However, there is no mention of Chessman in Kunitz and Haycraft's otherwise exhaustive Twentieth Century Authors. No Norton or Oxford anthology contains even a snippet of his prose, nor is there even a footnote on him in the underdog People's History of the United States by leftist historian Howard Zinn.

Even more telling: All four of Chessman's books are out of print, and the unpublished writings that were known to exist at the time of his death have never seen the light of day. Perhaps in one final act of brutal vindictiveness, the state of California destroyed them, the way they could never destroy the man himself.

Have we simply become less harsh as a society about sexual assault since 1948 or 1960? Or was this a specific case of amnesia? Were the guilt and regret, as Hardwick concludes at the time, so great over the snuffing of this gifted man's life that America put it out of mind as swiftly as she had the bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the World War II incarcerations of Japanese-Americans, the contemporaneous fire-hosings, bombings and shootings of civil rights marchers in the South?

The truth is more the latter than the former, because Caryl Chessman was not executed for his alleged crimes, necessarily.

As he put it in The Face of Justice, the last of what he considered his "trilogy" and the one he wrote in secret with death only a matter of hours away, he was killed because he made America uncomfortable. Though he was really just fighting for his life—not playing intellectual games or thumbing his broken nose—he was nonetheless seen, as he put it, as "a justice-mocking, lawless legal Houdini and agent provocateur assigned by the Devil (or was it the Communists?) to foment mistrust of lawfully constituted Authority."

"In those days, what I call 'the law of the rubber hose' prevailed in the land," said George T. Davis, a renowned defense attorney who was hired by an increasingly desperate Chessman in 1955. "There were no due process cases. There were no reversals of cases because of the activities of the police, because of the way they got confessions. There was no such thing as a Miranda rule. There were no such things as Fourth Amendment rights against search and seizures. The policeman went out and did whatever he thought was necessary. If he had to get a confession, he'd beat it out of the witness. When he got the confession, the confession stood up."

This, indeed, happened to Chessman, who was forcefully coerced into a confession while in custody in 1948. He later, on numerous occasions, recanted his confession, but by then it was too late. The state of California had already "thrown the book" at Chessman in his original 1949 trial, hanging the capital punishment on a now discarded kidnapping statute put on the books after the Lindbergh baby case. (Davis mockingly calls it "Stand still kidnapping!"). No legal body in the state wanted to touch Chessman after that, despite the many irregularities and tainted facets of his original trial.

"The state of California's attitude then is like President Bush's now," said the 94-year-old Davis, speaking from his home in Hawaii. "That is, 'well, he got his trial, so let's carry out the sentence'. No matter what. Expediency is all they were interested in."

Davis got involved in the Chessman case relatively late in the game. At that point, Chessman had already become a sort of Cal Ripken, Jr. of Death Row. As he put it in The Face of Justice, "I won the dubious distinction of having existed longer under death sentence than any other condemned man in the nation's then 179-year history. Day after day, I would go on breaking my own record."

The original trial was conducted under a cloud of suspicion, and Chessman, famously, made the mistake of representing himself in the courtroom, his blunt manner alienating the judge and jury. Further, the court stenographer died before a third of the proceedings had been transcribed; the remaining two-thirds of the transcription was done by a relative of the prosecutor, without Chessman's approval. That relative, a chronic alcoholic, made indiscriminate changes and couldn't even interpret his own handiwork in a court of law. In short, it was a travesty of bureaucratic bungling.

A contemporaneous study of the Chessman case by Mark Davidson in The Californian concluded that "Chessman was not convicted of rape, because in both of the robber-attack offenses for which he was condemned, the victims persuaded the bandit not to pursue coitus. The bandit instead had them perform fellatio..." (Undoubtedly, the same modus operandi of the NBA millionaire cited above). It would seem that so many questions were raised by the original trial that a new trial would be demanded. And surely in today's courtrooms, with a lawyer like Davis in his corner, Chessman would have gotten one.

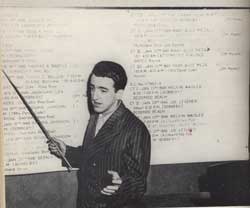

Davis had read all the stories about Chessman, followed his case and was fascinated by the man himself, and he confessed to wanting to meet this enigma in Cell 2455. He got a chance when Chessman contacted him; the defendant, it turns out, was just as curious about George T. Davis.

At the time, Davis had won national, if not international, notice for his successful defense of the condemned alleged Communist labor leader Tom Mooney. Mooney had been wrongfully imprisoned for 21 years, and Davis managed to wrest the case out of California's hands and place it in the lap of the U.S. Supreme Court; Mooney was freed. Davis was hoping to employ the same sort of strategy with Chessman.

"California was determined never to give him a retrial," said Davis. "Our only hope was to get the case into a federal court."

A bitter foe of the death penalty, Davis was at that point in his career only taking capital punishment cases. "We say taking a life is wrong and then set the example," said Davis. "No case is good enough to justify capital punishment. The Chessman case, of course, turned out to be the epitome of anti-capital punishment. My ability to propagandize, my ability to speak against that subject was opened up in a way that had never been done before...I won't say it's the first time that the world was ever thinking about it, but I'll say that because of the media and because of the nature of that case, I think that probably more people thought about capital punishment at that time than had ever thought about capital punishment before."

Chessman, many contended then, may have been innocent of the crimes for which he was convicted. These crimes (the two sexual assaults) stemmed from a string of burglaries and two assaults as the "Red Light Bandit," the nickname deriving from the modus operandi: San Francisco's lovers lanes were regularly visited by a cop-impersonating bandit who'd placed a blinking red light atop his car. The physical descriptions by victims did not come close to matching Chessman, and he was never identified by the assaulted women in a line up.

This is not to say that Chessman was an innocent or a naif, nor is it intended to minimize the pain and suffering of the victims. On the contrary, his memoirs, and his decade-long criminal record, make it clear that he was an inveterate sociopath on a collision course with prison. But he convincingly argued, time and time again, that he was innocent of the specific crimes that brought him his death sentence. "I wasn't a rapist who skulked and prowled around lovers' lanes. I was a bandit." This is not to say that Chessman was an innocent or a naif, nor is it intended to minimize the pain and suffering of the victims. On the contrary, his memoirs, and his decade-long criminal record, make it clear that he was an inveterate sociopath on a collision course with prison. But he convincingly argued, time and time again, that he was innocent of the specific crimes that brought him his death sentence. "I wasn't a rapist who skulked and prowled around lovers' lanes. I was a bandit."

And yet, he was also maddeningly hardheaded and quixotic in his methods of fighting what he felt was the injustice of his incarceration and sentence. This was interpreted by the public and the prosecutorial system as arrogance or coldheartedness, and he was duly depicted as a "monster" and "psychopathic wild beast in a cage" by the media, which, in that Cold War climate, was chillingly ultraconservative.

"If a bilious writer needed a target for his choler, I was invariably paraded out and given a sound thrashing, to the apparent satisfaction of all concerned," wrote Chessman.

Chessman, in short, did everything in his power, whether intentionally or not, to ruffle the feathers of those in authority.

He, for example, did not want lawyers to argue in court for him, though he hired them to help prepare his case and his multiple petitions for appeal. This hardheadedness is what got him his original conviction in 1949, the twin death sentences he ultimately was not able to shake, despite calling on the help of such wizards of the courtroom as Melvin Belli, Rosalie Asher and George T. Davis.

Chessman eschewed counsel because he possessed a "fierce insistence on remaining independent" and "was cursed with a mind that would not yield." "My soul," he famously announced, "is not for sale." He also admitted to having "developed the habit of doing my own fighting" and said that he "didn't trust people entirely."

But, ultimately, his fatal flaw was that he had a deep personal vendetta against the state of California, and he seemed determined to make the state pay at every step of the way. He was also fatally stubborn when it came to offering proof of his innocence of the crimes as the Red Light Bandit.

At the close of The Face of Justice, for example, as death is closing in on him again in 1957 (he got another last-second stay that lasted until 1960), Chessman maintained that he had "prepared a large and very special kind of package, which I placed where it cannot be found, seized, and suppressed or destroyed against my wishes. In that package is evidence showing indisputably that I am not the Red Light Bandit. Further, a document names and identifies the actual Red Light Bandits (plural), because in fact there are two..." Further, "if the executioner goes, my package will never be made public. If he doesn't go, it will be made public exactly fifty years from the day the bill for a moratorium on capital punishment is defeated."

He concludes, "How, possibly, could the police have made the 'mistake' of charging the wrong man with the notorious Red Light Bandit crimes? That also is something that is fully revealed in the Pandora's Box of facts I have prepared. I'll say just this much: the full documented story will add no luster to California's muddied and bloodied escutcheon."

But California did not care about muddied or bloodied escutcheons, whatever they were. Chessman had already had his day in court, and he failed to offer the "Pandora's Box of facts" at that time. They tolerated his petitions for hearings and stays of execution, but he would get no new trial.

So, why did they kill Caryl Chessman in the gas chamber in 1960, despite wide international outcry to spare his life? Despite tainted transcripts and uncompelling witnesses? Despite biased judges and petty, vindictive wardens?

Even after rereading the facts and the books and the newspaper accounts written at the time, these are still unanswerable questions. Indeed, the curious case of Caryl Chessman becomes "curioser" upon closer scrutiny, ranking as one of the most baffling episodes in American legal history.

As it stands—and making a wild guess from a distance of half a century—one can only conclude that they killed Chessman because he was a smart-ass. To paraphrase Ruben Patterson, Chessman may not have been no rapist, but he was not a great guy.

Or, as Chessman put it, "I am not generally regarded as a pleasant or socially minded fellow." Even Davis, 41 years after the fact, can't say for sure why they killed Chessman, though he agrees that his continued presence on Death Row was an ongoing embarrassment for the state of California, a broken cog in the judicial system.

"I can't explain his death and I can't understand why he has been forgotten either," said Davis. "Every capital punishment case that comes up has echoes of Chessman in it."

Davis personally was fond of Chessman. "He could be perceived as arrogant or self-assured at first meeting, but I thought he was a very decent, sensitive guy and I really got to like him," he said. "He was a very determined man, too, and a good writer."

Whatever anyone thought of Chessman then, or would think of him now in this more permissive age, readers of his writing can't help but be impressed with his iron will. He refused to let the walls and bars crush his spirit.

On eight separate occasions, like a character in a Dostoevsky novel, Chessman was within minutes of taking the elevator downstairs from Death Row to the gas chamber that, as in a Nazi crematorium, was housed just below the condemned men's cellblock. Then an eleventh-hour stay would be approved, and he would take the elevator back up to his cell. A lesser man would have been broken by this continuous ordeal—especially a man who had compelling evidence of his innocence and a reason to live—and Chessman willed himself not to give in to the darkness.

"The price I have personally paid for these extra Sisyphean years has been prohibitive," Chessman wrote in The Face of Justice. "My once bright dreams of a decent, creative future are maggot-infested.… My mirror tells me I am old and aged beyond my 35 years; the fatigue I feel is bone deep. I have an ulcer, and tonight it feels as though a hungry rat is gnawing at my duodenum. I fear for my continuing sanity."

Chessman was not just a good writer, as Davis suggests. He was something even more remarkable: a good thinker whose clarity of mind and ability to bring his thoughts directly to the page—given the circumstances, the harassment, sheer numbing stupidity, stench and chaos of San Quentin—evokes the great humanist philosophers. And the story of how he came to write The Face of Justice recalls something Solzhenitsyn would have endured at the gulag. As one reads his account of it, one can't help but wonder, "This happened in America?"

After the initial success of his Cell 2455, Death Row, Chessman was forbidden to write anything that did not directly involve his legal proceedings. And until the savvy Davis got involved, he was unable to gain access to the sizable sum of money generated by his two previous books.

So, he devised a means by which he got around the authorities, and the specifics of his grueling routine alone should be enough to inspire even the mildly curious to track down a copy of The Face of Justice.

Basically, it involved only working at night. He would write a first draft in longhand, then transfer that into shorthand, shredding and then flushing the longhand copy down his cell's toilet before daybreak. He camouflaged the shorthand with legal notations and code to throw off the men who searched his cell, stem to stern, each morning. He slept 4 out of every 24 hours, seven days a week. When he lost heart or hope, he pulled out a color supplement illustration of the gas chamber of San Quentin, looming like the jaw of death one story below him, and he studied it.

The resultant book reads like something that was not so much written, as wrenched, from a dark hole inside a man's soul. The clarity of his mind may have been due to the constraints of the prison itself, but that is only a piece of the answer to what created Chessman. His tale was unique, inexplicable and, given the helpless setting and hopeless prospects of success, downright heroic.

"A cat, I am told, has nine lives," writes Chessman. "If that is true, I know how a cat feels when, under the most hair-raising conditions, it has been obliged to expend the first eight of those lives in a chamber-of-horrors battle for survival, and the Grim Reaper gets it into his head that it will be great sport to try to bag the ninth. All pussy can do is spit. Homo sapiens can write books."

Titillated by the case, a prominent criminologist with the unlikely name Negley Teeters paid a call on Chessman. After his personal interview with the man, he said, "I came away from his cell convinced that here was a person who is too smart to live or to die. If he loses, society will have had its inning, but paradoxically it will have actually lost a battle. The ingredients that went into Chessman will remain a mystery."

One guarantee: By the time you finish reading Chessman's trilogy, and even his surprisingly snappy novel about boxing, The Kid Was A Killer, you understand why he went to his death unbowed. That is, you get a whiff of his "ingredients," and they hit with the force of an ammonia capsule.

"I am not guilty," he wrote at the end of his final book. "I am sure a future generation will listen." Chessman did not want to win on a technicality. He wanted to clear his name. It was, if one can believe this, the principle of the thing. He chose death, rather than to linger on yet another legal loophole.

Adding a macabre twist to his death is a story George Davis tells about getting a stay of execution on May 2, 1960, the day of Chessman's death. Knowing his petition would probably be rejected by the California Supreme Court, Davis arranged for a cab to drive him down the street to the U.S. District Court. He arrived at the former at 9 a.m. and had until 10 a.m. to get the stay at either court, as that was the exact planned time for the cyanide pellets to be dropped into the vat and the vapors to be released into Chessman's lungs.

As Davis expected, the State Supreme Court rejected the petition, 4 to 3. That was at 9:20 a.m. He navigated the six blocks to the district court and presented his petition there. Because the 15-page document was too long to read in the allotted time, Davis had driven out to the judge's house the day before (a Sunday) to personally give him an advance copy. But the federal judge still hadn't read it when Davis arrived at about 9:30 a.m. Davis was desperate.

"The judge took the petition, and he started to read it, page by page," he recalled. "As he started to read it and turn the pages, I kept watching the clock.… I saw that clock going from five minutes to ten, to four minutes to ten, to three minutes, and finally, when it got to just almost exactly one minute to, the judge said, 'All right, I'll grant the stay of execution.'"

But the prison had to be called. The execution had to be stopped. Davis begged the judge to let him dial the direct line on his chamber phone, to save precious seconds. The judge told him that his secretary would dial it for him, to just give her the number.

"I gave the number to the secretary. She walked into an adjoining office just a few feet away, and I thought 'Boy, this is the cliffhanger of all cliffhangers,' because now it's thirty seconds before ten, and she's dialing, but all it needs is to get to the warden. At about five seconds to before ten, the secretary walks out and says, 'Could you give me that number again, Mr. Davis? I must have misdialed it.' I gave her the number again, she dialed it again, she got the warden."

The judge told the warden to grant a stay of execution. The warden said, "I'm sorry, it's too late. The pellets have just been dropped."

Not knowing the frantic lengths to which his lawyer was going on his behalf, Chessman had prepared himself to meet death. Indeed, he met death with the sort of beatific dignity one finds in accounts of the final hours of religious martyrs or humanist "heretics" during the Reformation and Inquisition. He prepared a final statement, nodded, winked and smiled goodbye to those who had helped him and sat back as the dollar's worth of cyanide gas entered his lungs.

"When you read this," his statement read, "they will have killed me. I will have exchanged oblivion for an unprecedented twelve-year nightmare. And you will have witnessed the final, lethal, ritualistic act. It is my hope and my belief that you will be able to report that I died with dignity, without animal fear and without bravado. I owe that much to myself."

Davis went on to defend Benigno Aquino, a foe of the Marcos dynasty in the Philippines, and Jim Bakker, the PTL Club evangelist, among many other high profile cases in California and Hawaii. But he still expresses a measure of regret over the outcome of the Chessman case.

"Well, in a sense, you might say I lost the case," he said. "But I think that there were some things that were decided, even though it was a loser. For one thing...there has been no capital punishment in California since Chessman's. And this is with all the national trends and everything else. That's a rather remarkable thing, if you stop and think about it.

"Secondly, I think that as a result of my work in the Chessman case, there is one reason for capital punishment that was prevalent at that time but probably will never happen again, which is that no one will ever be sentenced to death who has not actually killed someone."

"What a case, though," Davis marvels. "You don't get many of those in a lifetime. Sometimes you just get locked into a great issue that almost justifies your existence. Because you can't really justify it on the basis of just making a living."

|