|

Critics are lug-worms in the liver of literature.

—Lawrence Durrell, "Monsieur"

All writers hate critics. From the lowliest book

reviewer on a weekly throwaway to the self-exalted Stanley

Fishes of the academic aquarium, writers view critics

as leeches on the vein of literature, eunuchs in the harem,

those who know the road but can’t drive the car,

legless men (and women) who try to teach running... you

get the picture.

In

The Tale of a Tub, Jonathan Swift suggested that

"it would be very expedient for the public good of

learning that every true critic, as soon as he

had finished his task assigned, should immediately deliver

himself up to ratsbane, or hemp, or from some convenient

altitude." And D. H. Lawrence once chided John Middleton

Murray:

"Either

you go on wheeling a wheelbarrow and lecturing at Cambridge

and going softer and softer inside, or you make a hard

fight with yourself, pull yourself up, harden yourself,

throw your feelings down the drain and face the world

as a fighter—you won’t though."

There’s

just something inherently absurd about those who can’t

making grand pronouncements about the abilities of those

who can.

I

should know. I used to be an academic, delivering ten-page

gobs of jargon to quarterly reviews and academic conferences.

That is, until I realized the stupidity of pretending

that the critic was just as important (nay, even more

important, saith the postmodernists) than the writer him/herself.

So I walked away from academia and moved to Europe to

write novels. I must admit I ate better as a critic, but

at least now I can sleep at night.

Under

normal circumstances, if I had read about a forthcoming

novel titled Death of a Critic, my heart would

soar with joy and I’d look forward to finding a copy

as quickly as possible. But I don’t live under normal

circumstances; I live in Germany. Not the Germany of BMWs,

Mercedes, pretzels and beer, but the Germany now in the

grip of a pair of anti-Semitic scandals that have caused

serious soul-searching about how Germans still refuse

to come to terms with their genocidal past.

Last

Wednesday, Surhrkamp Verlag decided to publish Martin

Walser’s controversial novel, Tod eines Kritikers

(Death of a Critic), after the Frankfurter Allgemeine

Zeitung (FAZ) refused to publish it serially. Walser,

75, is one of post-war Germany’s most important writers,

the author of such novels as Ein fliehendes Pferd

(A Runaway Horse) and Das Schwanenhaus (Swan

Villa). He is also now accused of being a raving anti-Semite.

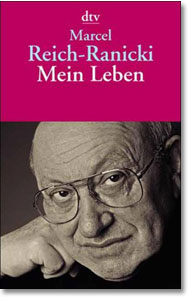

Marcel

Reich-Ranicki is post-war Germany’s most important

literary critic. The host of a popular TV program and

former FAZ literary editor, Reich-Ranicki, 82, is also

the author of Mein Leben (translated into English

as The Author of Himself), his autobiography, which

has sold hundreds of thousands of copies in Germany. Why

would anyone want to read about the life of a critic?

Reich-Ranicki is Jewish. His entire family was wiped out

during the Warsaw ghetto uprising. He is a survivor of

Auschwitz. And he returned to Germany after the war to

rebuild his life. He’s not your typical academic

lit-crit careerist drone. As Frank Schirrmacher, editor

of the FAZ, said, "The man is a symbol—of criticism,

of literature and of Jewish life in Germany after the

Holocaust." Marcel

Reich-Ranicki is post-war Germany’s most important

literary critic. The host of a popular TV program and

former FAZ literary editor, Reich-Ranicki, 82, is also

the author of Mein Leben (translated into English

as The Author of Himself), his autobiography, which

has sold hundreds of thousands of copies in Germany. Why

would anyone want to read about the life of a critic?

Reich-Ranicki is Jewish. His entire family was wiped out

during the Warsaw ghetto uprising. He is a survivor of

Auschwitz. And he returned to Germany after the war to

rebuild his life. He’s not your typical academic

lit-crit careerist drone. As Frank Schirrmacher, editor

of the FAZ, said, "The man is a symbol—of criticism,

of literature and of Jewish life in Germany after the

Holocaust."

Reich-Ranicki

believes Walser is one of Germany’s great contemporary

writers, although he left him out of his recent edition

of Der Kanan, Die deutsche Literatur (The

Canon of German Literature). When Walser was accused

of being an anti-Semite in 1998, after remarking that

Auschwitz should no longer be held over Germany as a "moral

cudgel," Reich-Ranicki came to his defense. The two

men have been friendly since the 1950’s.

So

why would Walser so transparently base the character of

Andre Ehrl-König in Death of a Critic on Marcel

Reich-Ranicki? There’s not much of a fictional disguise

in that name. The problem arises from Walser’s anti-Semitic

portrait of Ehrl-König. The novel drips with anti-Semitic

clichés about Jews, the most scandalous being Ehrl-König’s

penchant for fucking pregnant Goyische women. The

Jew as a sexual defiler is one of the oldest anti-Semitic

slights, later passed on in America to blacks as coked-out

rapists of white women. Why resurrect such nonsense? It’s

one thing when a newspaper in Saudi Arabia prints stories

about Jews sacrificing young children to use their blood

in Purim pastries; we can understand the ignorant hatred

of the Arabs. It’s quite another when a respected

German writer dabbles in old hatreds that his country,

at least at this rate, will never be able to live down.

This

time Reich-Ranicki has not come to Walser’s defense.

Speaking to Walser directly, he said, "This book

has upset both my wife and myself deeply and it pains

me to think that such a book could be written in Germany

in 2002 and by such a well-known writer." It pains

me, too, but it sure as hell doesn’t surprise me.

To

their credit, most newspapers and magazines in Germany

have agreed with Schirrmacher and Reich-Ranicki’s

assessment of this as-yet-unpublished novel (it comes

out June 26th). But there are still those who don’t

get it. Uwe Wittstock has written that German literature

"must keep a place for Jewish characters who are

not saints." Gustav Seibt suggests that if Reich-Ranicki

is offended, he should sue Walser—or shut up. Sensitive

fellows, these. And Walser’s own defense is that

the book is really a satire of anti-Semitism.

If

Walser believes that, he is an idiot. Seinfeld bombed

in Germany. Woody Allen films get almost no play. Last

month there was a documentary on TV trying to explain

to Germans why the Jewish-American sense of humor is funny

(I’m not making this up). The last true piece of

satire published in Germany was Thomas Mann’s Doktor

Faustus, and German scholars still scream themselves

hoarse denying it’s satire. German literature is

serious business. No laughing allowed! Thirty days in

the cooler!

The

arrogance of a nation that tried to exterminate an entire

race of people, but kept detailed records of names, dates,

and family histories, lives on. In addition to this literary

scandal, there is also a political scandal rocking Germany

at the moment. The FDP, the party with which current chancellor

Gerhard Schröder hoped to build a coalition for his

reelection, has been tarred-and-feathered with accusations

of anti-Semitism. Jürgen Mölleman, the deputy

chairman of the FDP, and his moronic stooge, Jamal Karsi,

a German of Syrian descent, have pretty much committed

political suicide by referring to the Israelis as "Nazis"

and accusing Michel Friedman of the Central Council of

Jews of fomenting anti-Semitism with his criticisms of

their stupidity. See, when the Jews fight back it promotes

anti-Semitism. It’s really all our fault. Schröder

is now expected to lose in September to his rival, Edmund

Stoiber.

If

there is a bright light in all of this, it’s that

the German media is now full of stories about Germans

and the continuing specter of anti-Semitism. Sterne

ran a story about Jews living in Berlin called "Unser

Leben hier ist nicht normal" ("Our lives here

are not normal"). I can surely vouch for that. There

was also a cartoon in that issue (which is now pasted

to my refrigerator door) of Möllemann and Jamal Karsi:

"Wir sind keine Antisemiten" ("We are not

anti-Semites"). Möllemann smiles, and Karsi

replies, "Wir tun nur so!!" ("We only act

like it"). Maybe there is a small place for satire

in German culture after all.

And

just the other day, like a scene straight out of a Philip

Roth novel, in the FAZ there was a photo of Germans holding

signs reading "Wir lieben unsere jüdischen Mitbürger!"

("We love our Jewish fellow citizens"). Now

they like us! Perhaps we should just close up shop in

Israel and come back to the open arms of Deutschland (Roth

himself skewers this idea brilliantly as "reverse

Diasporism" in his novel The Counterlife).

I’ll be honest with you: even I am starting to wonder

why I stay here.

Should

Walser’s book be censored or perhaps even burned?

Of course not. Let the world see his stupidity in print.

Let the literary marketplace drive him into the obscurity

he so rightly deserves. I may hold a low opinion of critics,

but sometimes even they deserve the respect we should

show more often to our fellow citizens. Hopefully, Marcel

Reich-Ranicki’s autobiography will sell hundreds

of thousands of copies here, while Walser’s novel

quickly goes out of print. Unfortunately, there are far

too many people who want to believe the kind of scheiss

Walser shovels. And not all of them live in Germany.

|