|

"The

old politics had parties, policies, planks, opposition.

The new politics is concerned only with images. The problem

in the new politics is to find the right image. Image

hunting is the new thing, and policies no longer matter

because whether your electric light is provided by Republicans

or Democrats is rather unimportant compared to the service

of light and power and all the other kinds of services

that go with our cities. Service environment's the thing

in place of political parties."

This

is Marshall McLuhan speaking to the students of Florida

State University in 1970. Virtually forgotten in the years

after his death in 1980, McLuhan was the sixties media

guru who predicted the death of the book, yet who saw

his own books go out of print and his own reputation consigned

to history's dustbin. McLuhan was described in the eighties

as "laughably inadequate as an intellectual guide to our

times," but his reputation was revived at the beginning

of the nineties by the online generation and the spread

of the Internet. Nevertheless, outside of a handful of

familiar mantras–the medium is the message, the concept

of the global village–and a famous cameo appearance

in Annie Hall, as a cultural figure he is a museum

piece who remains ahead of the times. His powers of prescience

are uncanny, and his emphasis on the role of technological

evolution rather than biological and genetic determinism

is a vital tool for negotiating the brave new digital

world.

Through

his own idiosyncratic modes of communication–part

medicine show huckster, part Zen master–he foresaw

how television rather than the voting booth would win

elections. He may not have foreseen the elevation of Dubya

to the White House–banned by nervous advisors from

committing his inarticulateness to e-mail–but he

predicted the global village of e-mail culture, and he

imagined cybersex encounters between people across the

world decades before the technology was in place. His

aphorisms, what he called probes, included envisioning

the computer age as "an extension of the human nervous

system" just as clothes were an extension of the skin,

the wheel an extension of the foot, and the book an extension

of the eye.

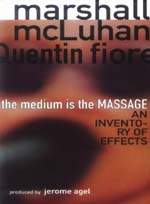

Last

year California-based Gingko Press launched a major publishing

program that extends through 2007 with new editions of

McLuhan's late sixties classics The Medium Is the Massage

and its sequel, War and Peace in the Global Village.

Forthcoming are a new edition of his first book The

Mechanical Bride, an unbound box of eighteen McLuhan

essays–the first of three such volumes–and Anthology:

A Book of Probes, containing McLuhanisms from his

entire oeuvre.

McLuhan

is important because he was the first to articulate a

radical and contemporary understanding of the new media

and the information environment. He noted, accurately,

that in times of innovation "we look at the present through

a rear-view mirror. We march backwards into the future."

The corporate invasion of the Internet is an example of

this. As the virtual bubble created by venture capitalists

evaporates into the new dot.gone culture, the prospect

of a technological meltdown affects us all. The medium

itself is under threat. With McLuhan to massage our brains

with his probes, we can stop looking backwards and start

looking around us at what virtuality really is.

|

In

the 21st century, The Medium Is the Massage is

both a classic Pop Artifact and a futuristic joke manual

for negotiating our new media. It doesn't even matter,

argues McLuhan, if you never log on, turn on, tune in.

"Electronic information comes from all directions at once,

and when information comes from all directions simultaneously,

you are living in an acoustic world [cyberspace in today's

parlance]. It doesn't matter whether you're listening

or not, the fact is you're getting this acoustic pattern."

The

Medium Is the Massage was his one bestseller, the

book that put him on the cover of Time. It is of

its time, of course, but its matter, its message, is way

ahead of us still. We are still looking back, while McLuhan

the media guru never did. He didn't even write his books,

but dictated them. He rarely revised. He was careless,

too, of his own legacy and reputation, instigating crackpot

schemes such as an underwear deodorant called Prohtex

to enhance "legitimate body odors." Thus the culture that

made him an icon soon tired of him.

For

The Medium Is the Massage he actually provided

only the book's title. Jerome Agel collected the McLuhanisms,

the "probes" that could be as enlightening as they were

confusing, and Quentin Fiore created the design. Together

they forged a sixties classic infused with the vernacular

of the times, but whose implications transcend the era.

The book's text-graphic interface carries its own political

message. One passage quotes Indonesia's President Sukarno

on the revolutionary role Hollywood's depiction of Western

affluence played in the post-Colonial upheavals of Asia.

I Love Lucy, it seems, can move mountains as much

as Chairman Mao. Black activists such as Angela Davis

numbered among McLuhan's students. What liberation ideologies

did they take with them from his classes? His revolutionary

focus on the medium exposed American society's subliminal

messages on race, gender, age, consumption. McLuhan's

was the meta approach. Where he first trod, political,

radical text artists such as Barbara Kruger later followed.

|

The

Gingko Press edition is a facsimile of the original, and

though historians of culture may well have a dog-eared

first edition somewhere on their shelves, this new edition

offers the full-blown head massage to a new generation.

Open it, and you're opening a time capsule, electronic

culture's first prophetic book. Its spiky juxtapositions

of text and image, sometimes explanatory and often disturbingly

dislocated, are some way from McLuhan's early, notoriously

dense, difficult texts, The Mechanical Bride (1951),

The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding

Media (1964). McLuhan gained a reputation early on

as a bad communicator who nevertheless had brilliant insights

into modern communication. To his critics he came to represent

obscurity and pretension; to his supporters he was a right-brained

genius. It didn't matter if what he said was wrong–and

it often was–what was important was the method, and

how it made you stop and consider the defining environments

of communication you had never considered before. A lover

of puns, of wit over reason, an indefatigable talker,

and a voracious reader, McLuhan himself remained unplugged.

"I am resolutely opposed to all innovation, all change,"

he wrote, "but I am determined to understand what is happening,

because I don't choose just to sit and let the juggernaut

roll over me." As such, McLuhan is in some ways an odd

choice for the Internet generation's guru. Born in 1911

in Edmonton, Alberta, and a convert to Catholicism in

1937, a religious mystic and political conservative, he

was already in his fifties by the time he became the sixties'

oddest youth icon. Nor did he engage with the actual media

he studied–he was more bookworm than couch potato.

The mediums he studied were personally foreign to him.

His

early academic works argued for a kind of technological

determinism, stretching back to the discovery of the alphabet.

Just as the historian Lyn White suggested that the technology

of the stirrup created the Middle Ages, so McLuhan argued

for an explicit awareness of the technology of communication.

Civilization, he says, proceeded through four major stages.

The earliest oral tribal cultures were superceded by the

technology of the alphabet, which led to the concept of

the individual, because writing is a visual medium; we

don't read collectively, but alone. The invention of moveable

type drove the linear development of civilization, as

well as concepts of nationhood and conquest, while the

technology of the new media–the multimedia–has

returned society to an acoustic, oral tribalism. The mode

of society's communication is for McLuhan much more significant

than its content. Behind the effects lie the pattern,

and it is the pattern with which McLuhan concerned himself.

It is the pattern, he says, in which we see where we really

are. Take a newspaper, for instance, with its headings,

subheadings, stand-firsts, advertisements. "People don't

actually read newspapers," he remarked, "they get into

them every morning like a hot bath." Rather than climbing

into them himself, McLuhan was more inclined to test the

temperature, measure the level–and pull the plug.

By

adopting the McLuhan mindset, you can make your own media

probes to embark on your own head massage. His legacy

is more medium than message. It is yours to use; make

of it what you will. The Medium Is the Massage is

a wakeup call to look around you rather than in the rearview

mirror. McLuhan was neither cheerleader nor Cassandra

for the new medium. "Value judgements create smog in our

culture," he wrote, "and distract attention from processes."

By identifying the processes, we can liberate ourselves

from them. It is up, or down, to us. We may even end up

like the private McLuhan, who yearned for the pre-electronic

era and wished, while aware of its futility, that the

global village he saw shaping up before him had never

arrived.

The

Medium is the Massage

and War and Peace in the Global Village are published

by Gingko Press, California.

|