|

There’s a scene halfway

through Big Bad Love where Leon Barlow (Arliss

Howard) sits—wrapped in a bedsheet—on his farmhouse’s

front porch sipping a cup of coffee as the sun dawns on

a new day. Seems idyllic doesn’t it? It is if you

haven’t seen the first hour of the film. Leon is

an unemployed, unpublished writer, and he’s just

capped off a rip-roaring weekend bender. So, what’s

great about this porch scene? Nothing, actually. But,

it’s the first time—of many—where I thought:

"It sure doesn’t look bad to be a struggling writer

in Mississippi."

The movie is adapted from

a collection of short stories (Big Bad Love) written

by Larry Brown. The old adage, write what you know applies

for Brown; both he and his fictional offspring hail from

Mississippi; both served in the Armed Service; both struggled

before making their literary name. To Howard’s credit

the nuances of southern-writer seem dead on accurate.

By nuances I mean Howard’s drawl, his spitfire temper

but laid back approach. However, the first crack in the

film’s authenticity is Howard’s physique. Writers

don’t have bodies like flyweight boxers.

Barlow is an alcoholic—typical

of nearly every writer portrayed on the screen—and

his Mississippi life is a living nightmare. His best friend

is a millionaire rabble-rouser, Monroe (Paul Le Mat),

who he peruses the local haunts with before passing out

in his single bed, or in a few instances, his bathtub.

His relationship with his ex-wife is strained. He has

two kids; the youngest, the daughter, has a medical condition.

He and Monroe paint houses for income. He churns out the

pages by the dozen but his mailbox is stuffed, daily,

with rejections.

|

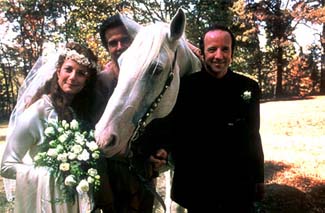

Almost all of Barlow’s

pain comes from his divorce. Although, aside from a flashback,

where the 8mm movie of his wedding day runs backwards—we

are given nothing of his relationship with Marilyn (Debra

Winger). Barlow has the capacity for passion/feeling but

there’s a disconnect between his heart and soul.

In the attempt to fuse them (and his marriage) back together,

he escapes into his fertile imagination, which intensifies

his pain, thus he hoses down the whole mess with beer.

Unfortunately, instead

of portraying Barlow with a stifling, if not debilitating

exterior life—Howard (as director) has chosen to

glamorize the writing life by relying on and exploiting

every known writer cliché. This happens in most

movies featuring the protagonist as a writer. Yes, there

are many writer movies out there. To name just a few:

John Mahoney’s WP in Barton Fink (who is purposely

a stereotype—those clever Coen Bros.), Patrick Dempsey’s

lead character in Happy Together, Mickey Rourke

in Barfly, and more recently, Colin Hanks' character

in Orange County. Granted, the two teen movies

avoid the alcoholism trope, still both are unable to balance

their inner-selves with the exterior world.

|

Has the writer-protagonist

become a stock character for any/all movies wanting to

portray an artist out of touch with their sensibilities?

Show the audience a writer and automatically they see:

1. Searcher 2. Untapped passion 3. Pain, and thus by stereotype

baggage alone the director is excused from spending twenty

minutes of a film’s precious 145 setting up the protagonist’s

plight. Barlow, of course, is all of the above: searcher;

fighter (with persistence greater than Phillip Marlow

and a body like Sugar Ray Leonard). He’s up to his

neck with extraordinary pain (divorced, rejected, sick

kid)—but the movie skips across the surface of these,

using them only as touchstones of Barlow’s miserable

life.

PAIN+IMAGINATION+BEER=MORE

PAIN/BAD LIFE is the equation Big Bad Love tries

so valiantly to portray, but mong all the drinking, carousing,

bathtub passing out, failing family relationships, irresponsibility,

sick child, unemployment—all of which is played over

a sound track by R.L. Burnside and Tom Waits—what

we see best is Barlow’s fertile imagination. This

is the one innovative and wonderful success of the film.

Jay Rabinowitz’s (Homicide: Life on the Street,

Requiem for a Dream")

dexterous editing stitches together Leon’s internal

vision like a bizarre-surreal-magical-realism hootenanny

of clown masks, railroad cars, water filled houses, and

‘Nam flashbacks. It saves the film from being trite

writer escaping his demons to writer escaping his demons

with MTVesque editing.

The acting nearly saves

the film, too. Debra Winger, Patricia Arquette, and Paul

Le Man are all very good at rounding out Howard’s

world. But it’s not enough.

In the end, Big Bad

Love romanticizes what would otherwise seem an ugly

and horrid life. I have the suspicion that I was suppose

to feel, and maybe even shed a tear, as I watched Barlow

struggle with his pain, waiting for his break. It made

me, instead, want to move to Mississippi—the writing

life down there doesn’t seem too bad.

|