|

Out

in paperback this month, David Hajdu’s Positively

4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan,

Mimi Baez Farina and Richard Farina (North Point Press)

is part biography, part popular music history and part

Greenwich Village travelogue, circa 1962.

It’s

obvious why a writer of Hajdu’s expertise—his

last book was on jazz vocalist Billy Strayhorn—would

want to have a go at Dylan and the elder Baez sister.

They were folk/rock royalty, the couple everyone talked

about—they were Britney and Justin with talent.

But

why would Hajdu devote so much time and energy to documenting

the lives of Joan’s little sister and her husband

Richard? As Hajdu points out in his richly-reported book,

Mimi was, in some ways, a greater talent than her better-known

sibling. A preternatural beauty and a widow by the time

she was 21, hers is an irresistible story. And Farina,

well, he was a storyteller, a musician and a writer of

such skill that his only novel made a jealous man of close

friend Thomas Pynchon. "Holy shit man," Pynchon, the most

inventive novelist of his era, wrote after reading the

manuscript that became Farina’s only novel, Been

Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me. "How would ‘holy

shit’ look on the book jacket? What I mean is you

have written, really and truly, a great out-of-fucking

sight book."

Hajdu

recently spent six months with Wynton Marsalis for an

upcoming piece in Atlantic Monthly and has begun

writing a book about mid-century comics. He is on tour

again this month to support the Dylan-Baez-Farina paperback,

but he took time out recently to talk about the book,

the four characters at its heart and how he managed to

get in touch with the famously reclusive Pynchon.

|

Gadfly:

For pretty obvious reasons, a lot of other writers

have focused exclusively on Joan Baez and Dylan. Why did

you decide to focus on all four of these people?

Hajdu: There are a number of reasons. I was interested

in the Farinas as a point of contrast. By telling the

story of all four of them you start with four people who

might seem to have the same kind of potential. You have

two sisters who are both musically gifted. Practically

everyone who knew them both—including Joan—thought

that Mimi was the superior musician, as a guitarist. Joan

had a better voice, and Joan had something else—but

the similar genetic makeup. So the two of them are a case

study in what it takes to succeed in this culture, and

also of the role of sibling relations in the development

of artistic lives.

And

then Dylan and Farina are similar points of contrast.

Dylan's detractors—I'm not among them—have often

painted him as an overly ambitious young man who used

everything he came in touch with to his benefit. But much

more than that accounts for Dylan's success as an artist

and as a cultural figure. Richard Farina was much more

ambitious. Richard Farina was infinitely more ambitious.

So what if you have two people, one who has great ideas—Richard

Farina—and ambition on a monstrous scale and then

someone who also has great ideas [Dylan] but a different

kind of talent, and a deeper talent? And then the relationships

between all four of them were intertwined. So it’s

more than just the effect of sibling relationships on

careers, but also fraternal relationships. The four of

them are an irresistible study; it was a little laboratory

for me.

You explain how Joan Baez enjoyed more early success

than almost anyone in the folk scene, including Dylan.

What effect did her popularity have on other artists and

the scene as a whole?

It's immeasurable, it's absolutely immeasurable. Joan

was the first young star in the folk milieu. She made

a music that had different associations, she made it cool

and young and hip and she helped a whole generation connect

with the music, connect to folk music in a way that was

related to their identity and their concerns. You had

people seeking an individual generational identity in

the shadow of the World War II generation, in the shadow

of a generation that won The War, seemed to rule the world

and was infusing everything in the culture with a kind

of bombast and power—the confidence and the kind

of overt the top rah-rah Americanism. Big cars, jets,

confidence in anything that was American, mass-produced,

commercial. Folk music was played by older people and

had been around forever. It was folk music for

goodness sakes. Young people were able to see that as

an antidote to everything their parents represented. For

once they had someone their own age to connect to. Joan

was really the Elvis figure, not Bob.

You

alluded to this before, I think. Like a lot of artists

who came after him, Dylan sort of reinvented himself on

a few occasions, didn't he?

Yeah, he sure did. But so did I. I don't know about you.

That's kind of the nature of what it means to be American.

It's part of the American ideal, it's part of the great

promise of this country. It's a New World so you can become

a new person here; I think I used a line like that in

the book. And especially in show business, there's a long

tradition that predates America of reinvention in show

business. But the irony of it in the case of Dylan and

his peers and Joan, too, was that they performed their

roles and adopted false personas in the nature of authenticity.

That's really the irony of it. On the surface they were

challenging the artificiality of their parents‘ generation,

they were challenging the Vegasy artificiality of Vic

Damone and that whole ilk of singers. But what they were

doing was certainly just as much a pose—but in the

name of authenticity. It’s really very peculiar and

complicated.

Dylan's first record was almost never released, you

say, and when it finally was it sold pretty poorly, didn't

it?

I don't have the numbers in front of me, but it was a

disappointment. John Hammond, who had signed him, was

under tremendous pressure to drop him. In the halls of

Columbia Dylan was derided as Hammond’s folly. And

the record is quite good, but it’s not the Bob Dylan

we know now. He hadn't yet found his voice, certainly

as a composer. And it's a remarkable act of prescience

on Hammond's part that he signed this guy at all. He certainly

didn't see any songwriting genius in Dylan at that point.

He hadn't written works of genius yet, he had only written

a handful of things of any merit. But then Dylan started

composing and [1963’s The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan]

seems like some kind of miracle following the first album.

The rate of his growth was just breathtaking. In a matter

of months he was on another level, from one album to another

album to another album. He just seems to be almost a different

artist. It's the same kind of growth that you could see

in the Beatles just a few years later. There's practically

no precedent for it in the music of subsequent generations.

Dylan and Joan Baez tapped into sort of a cultural

moment as much as a musical movement. How were they able

to pull that off?

It was kind of remarkable. It was this odd time when it

was a trend, it was chic to be serious, introspective,

poetic, socially conscious, to apply self-sacrifice to

social causes. Why? The peak of the Civil Rights movement,

the Vietnam War was just catching fire, beginning to become

a controversy in this country. The Cold War was at a peak.

I was a kid in those days, and I remember being in school

with crayons and having to draw pictures of how we would

design our fallout shelters. And that was a class assignment.

[Dylan and Baez] gave voice to those concerns through

a music that seemed appropriately serious and had the

right kind of gravitas.

You

talk about the legend surrounding Dylan's going electric

at the Newport Folk in '65. That's sort taken on mythic

status over the years and it's become overblown to a certain

extent, hasn't it?

Well, it definitely has. I read the contemporary reports,

and it was not seen as a cataclysm at the time. It was

absolutely impossible that most of those people were surprised

to hear Bob Dylan playing with a rock band. "Like a Rolling

Stone" was on the pop charts. You couldn't drive to Newport

without hearing "Like a Rolling Stone" the whole ride.

Bringing it All Back Home had come out something

like six months before that. "Like a Rolling Stone" was

his second rock and roll single/ folk rock single. So

there's no way that everyone was shocked. They might’ve

been shocked if he came out with a folk guitar—that

would’ve been a shock.

Now

there were some complaints about the performance that

day. But they didn't dominate the audience reaction. The

nature of those complaints is up for debate. Maybe it

was the sound system. The Newport Folk Festival wasn't

wired for a rock band. The sound system wasn't set up

for that kind of performance, and surely some of the diehard

old-line folk purists did object to the commercialism

that they associated with rock n roll. It was popular

music, my God. Folk music can’t be popular.

The moment has been reinvented over the years because

it serves a handy function. Every generation needs not

just great music and great artists, we need great moments.

We just need them and that became one of them.

Thomas Pynchon was Farina's best man, as you note,

and you quote Pynchon several times in the book. How were

able to pin him down?

He was very generous with me and helpful and I think that

was out of respect for his old friend Richard. He responded

well to my questions, by fax, by way of an intermediary.

One day I came home and the fax machine is churning and

it was answers from Thomas Pynchon. I was so excited about

it. He had never done this before. I couldn't sit still.

I had to go out and take my dog for a walk, just kind

of run around the block. My mouth was parched so I put

the dog on a post and I ran in to get a cold drink at

the deli. I came back to the house, pacing, the buzzer

rings, it's the police. I had left my dog tied to a post.

Could I say I'm sorry, officer, I just got a fax from

Thomas Pynchon? I'm sure he’d understand.

|

Farina’s

novel is still in print but you say near the end of the

book that he never started his second one, and you explain

how it was going to be a memoir of his times with Dylan

and the Baez sisters. Did you in a way write the book

that he never got a chance to?

That was not my intent. I had put a couple of years of

work into the book and done probably half the interviews

when I found that out from his editor. I was surprised

but it just seemed like a poetic convergence, so I loved

hearing that fact. But I didn't set out to write the lost

Richard Farina novel. I did have that fact in mind when

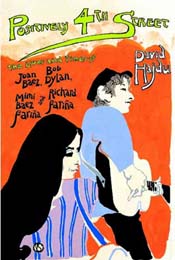

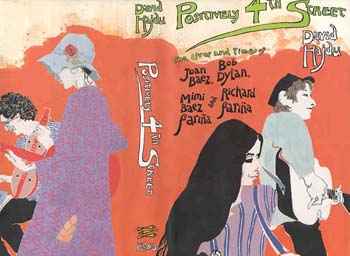

I asked [artist] Eric von Schmidt to do the cover. It

was a painting inspired by a poster that he made for a

concert that Joan and Bob did. He repainted it and added

Richard and Mimi in the back. I had that in mind because

he had only ever done two book jackets before (Farina’s

novel and a collection of his previously unpublished work).

So no I didn’t set out to write the lost Richard

Farina book, but I found a lot of pleasure in the convergence.

|