|

In Cameron Crowe’s

film Singles, Matt Dillon’s character Cliff

Poncier tells a journalist (played by Crowe himself) that

despite their apparent lack of success, his band, Citizen

Dick, is huge in Belgium. The comment on one hand humorously

illustrates the desperation of a man trying to claim some

validity despite a lack of success in his home city of

Seattle. On the other, it is an attempt to prey on the

mysterious mythology of gaining a following in the foreign

land of Europe, where somehow, these more highly-cultivated

lovers of art recognize genius where we cannot.

It is both a marketing

tool and a paean to art. Music labels release different

versions of the same albums, with additional bonus tracks

for European audiences. This can only benefit the labels

and the bands, because such releases capitalize on the

adoration of American pop culture while simultaneously

allowing these overseas audiences to be rewarded something

superior than their American counterparts—who, if

they care enough for the band, will still go out and spend

extra cash for it as well. Everybody wins, except for

the poor schmoes who shell out their hard-earned cash

for the Dutch import of some album because it has an extra

live track hidden at the end. And quality is not an issue,

of course; the same is true for a release from Bob Dylan

or Beck as it is with some new flavor of the month, giving

a nice fabric softener to their emperor’s new clothes.

|

|

The

Olympia Theater in France in 1976

|

This extends beyond music.

What has mass appeal in Europe often has only a select

audience at home. Forget the tired cliché of Jerry

Lewis fans in France—I’ve never seen or heard

of them, not a one; the seriously adored honorary American

darlings of Western Europe are those such as filmmakers

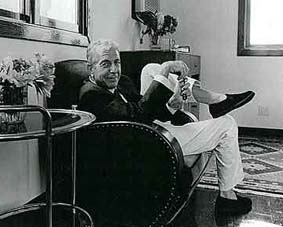

Woody Allen, Jim Jarmusch, Todd Solondz, singer Leonard

Cohen, and author Paul Auster, to name a few. And the

Coen brothers, until their recent domestic success began

to even the score. Jazz music itself is far more widely

appreciated in Europe than it is in the mainstream of

the U.S. One suspects there is a certain smugness to it

all; not only are they appreciated for their works, but

the very act of Europeans proclaiming these North Americans

as formidable talents—those who are not nearly as

appreciated in their own land—is a relished statement

of cultural superiority. As in, "how can you all be so

dense so as to not see wonderful art right under your

nose? You know nothing." Maybe most of us don’t.

After all, when we walk into national video chains, we

are greeted with 30 copies of the newest big releases,

guaranteed to be there, and one copy, if we are lucky,

of Woody Allen’s films.

The Internet, that unruly

friend/foe of pop commerce has opened borders as expected.

It has torn down some of the pretentious PR walls that

exist, dispelling some of that mystique. Fans of bands

can read the set lists each day of a European tour and

can easily download what were previously (and therefore

expensive) non-U.S. releases from either bands’ own

sites or file sharing programs. Just over a year ago,

I paid $30 for a Japanese import of jazz/blues musician

Terry Callier’s most recent album, not available

in the U.S. at the time. Ironically, it was recorded in

Chicago, where I was living at the time, yet I had to

order all the way from Japan to get it. And when it arrived,

it had the Japanese overlay, giving this, an album of

nothing but Americana, the aura of Asia, and I was more

than a little seduced by it as something of greater artistic

value.

Film and literature is

translated or dubbed and more accessible to foreign audiences

than music, making a relationship between musician and

foreign audience unique. Perhaps the most prime example

of this is Leonard Cohen; the opening page of his official

website, leonardcohen.com has links to microsites for

fans in Belgium, France, Holland, Italy and Poland. His

albums, like the films of Woody Allen, have greater success

in Europe than they do on his own continent. And Paul

Auster—who lived in France years ago and speaks French—writes

in English, then is translated by others. Imagine that,

a master of words being more appreciated in a nation where

they aren’t even his words being used. Ironic? Who

cares. Those who know him and his work in the United States

only see the Euro-adoration as a boon to Auster’s

street cred. And if it makes us American readers a little

more cosmopolitan in the process, all the better.

|

Another issue at work here

is the concept of the release date, and how it is selected

for different countries based on reputation and appreciation

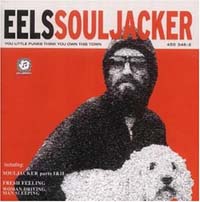

or for entirely different reasons. The Eels found more

success in Europe, with greater albums sales than in the

United States. Souljacker, the latest Eels album,

was released in Europe almost 6 months ago and still won’t

be released in the U.S. until next week. Why is that?

It is a bit of a sonically difficult album and except

for a few tracks it is less radio-friendly than the last,

Daisies of the Galaxy. Is an initial European release

a way to have it embraced where the record company is

more certain of its success, which could in turn prompt

a larger reception back home? The "Big In Europe" strategy?

Or could it have anything to do with its sardonic, flippant

tone? This is pure conjecture, but it might be related

to the title track itself, which includes the lyrics:

Johnny don't like the

teacher

Johnny don't like the school

One day Johnny is gonna do somethin'

Show 'em he's nobody's fool

Oh yeah

This may seem inconsequential

as controversial lyrics go, but Sept.11th aside,

jokes about school shootings are not taken lightly in

the States. And this wouldn’t be the first time for

something like this: the film O, last year’s

modern version of Othello, was completed in 1998 but its

release delayed due to the rash of high school violence

like that depicted in the film. As for the Eels, the band’s

website offers no explanation for the delay except an

acknowledgment of the injustice of the wait, and an apology

of sorts by making it a double album with some rarities

and (European) B-sides that is adding to the price of

the album. Regardless of the reason for the delay, the

point remains that the Eels like other bands, have a specific

relationship with European fans that differs from those

in North America. And now the band is giving something

back to its American fans that normally goes to those

in Europe.

***

As for cinema, the Internet

has erased the notion of targeted, slow release. Word

of mouth travels instantly now. A kid online in Europe

or Malaysia can watch trailers for all the latest films

being released in the US months and months before the

specifically timed ad campaign begins in his country.

Without even intending to, the Internet allows for global

advertising campaigns. And the studios have caught onto

this. Who are they to stand in the way of that and not

capitalize on universal interest in a film? Five years

ago, most American films being released in France had

come out in the States on average almost half a year earlier.

Now it is three months, even less. Harry Potter,

Lord of the Rings and the upcoming Time Machine

as well as Star Wars Episode II have initial

release dates within days of the American premieres. But

what of American films released far in advance overseas?

Sure, some of this had to do with funding agreements,

particularly if some of the production money comes from

European countries, for example. The

films Donnie Darko, Storytelling and the

upcoming Human Nature have been playing in France

for months. All three have highly bankable American movie

stars in them, but share the trait of having complicated,

genre-bending plots. Storytelling, Todd Solondz’s

first film since 1998’s Happiness, has a fairly

graphic sex scene that features red boxes covering the

naked bodies of the couple—a pre-emptive protest

again the MPAA’s inevitable verdict of an NC-17 rating,

commercial suicide (and possibly forbidden according to

Solondz’s contract which might—as other filmmaker’s

do—stipulate that he can do anything as long as the

film gets at most an R rating). All the commentary about

these red boxes point out how the film’s European

version does not have any kind of censoring, just as Kubrick’s

Eyes Wide Shut before it. Again, the idea of European

audience maturity, contrasted to the reputation of U.S.

repression. And it is without a doubt that U.S. fans of

this or other films will patiently wait for the DVD, in

hopes of seeing the "real" movie, giving rise to the idea

of European versions as the true and pure form of American

works.

|

In addition to the culture

gap between nations, is a prioritizing of the dialogue

between fans, press and musicians in Europe. John Ondrasik,

the singer/songwriter of the popular band Five For Fighting

sees a largely different perspective overseas. "The most

pleasing thing to me has been the sophistication of the

international press," says Ondrasik, whose album America

Town has sold more than half a million units and is

just starting to gain notice overseas. "I love the fact

that [with European journalists] we spend 90 percent of

the time talking about the themes of my record beyond

just the musical component. Sadly, in the States this

is a scary commodity.

"Obviously, marketing a

record called America Town is a bit challenging

internationally though at the end of the day it's still

about the songs… and frankly the themes of [the album]

are surely not unique to America." For Ondrasik’s

first album he teasingly recorded a hidden track called

European B-Side, a coda of sorts that brings together

the themes of the album.

The question arises, though,

about whose expectations are being catered to by press

and industry. Is "substance" really a commodity in the

United States? Has Jefferson’s "marketplace of ideas"

really boiled down to the lowest common denominator? Or

is that just a bunch of hooey, the common complaint of

American disinterest in art beyond the black and white?

Lately, these questions have spilled over into the arena

of politics as well. Not a few European leaders have criticized

President Bush for his Reagan-esque oversimplification

of conflict and world affairs with his self-ascribed "Texas-style"

lingo, and his clearly defined notions of Good vs. Evil—with

respect to the war on terrorism but also beyond that.

This is an embarrassing legacy of Americans as not even

so much narrow-minded or puritanical, but as unable or

unwilling to explore and accept the complexities of both

history and current events. An obvious exercise in generalizations

to be sure, but it all feeds our mutual notions of what

is worth our time and theirs.

And yet, couldn’t

some of this culture appreciation be this same over-simplication

in the other direction? The mystique of New York City

is vital to the works of Woody Allen and Paul Auster in

a way that works as a travelogue of sorts. Nashville-based

non-country musician Josh Rouse admitted that many European

journalists would ask him the same questions about Garth

Brooks and country music over and over because he was

from the same region in the U.S. And there is no doubt

that Things American have a high value of currency overseas,

if at the present time, these sweet thoughts are limited

to our pop culture.

***

Still, Auster,

Cohen, and the late Jeff Buckley… ultimately these

are artists that show respect—props, if you will—to

other countries. Foreign audiences reward them with their

attention and support for what they see as larger

world views, beyond the "americentricism" of other pop

culture figures. Contrary to belief, the French don't

hate people that don't speak their language. They would

just respect you a whole lot more if you at least spoke one

more, any other, in addition to your mother tongue.

|

|

Leonard

Cohen

|

Depending on

the audience, being Big In Europe is definitely a boon,

revealing a higher sense of cultivation, a special status,

something to aspire to. Or alternatively, it is commercial

suicide, the equivalent of being a communist: Obscure,

contrarian radically difficult. But at least there aren’t

any subtitles. Sure, Europeans love themselves some Hollywood-grown

no-brainers, but we all have guilty pleasures. That isn’t

the official m.o. of cinema or music over here. Once,

years ago one of the "Why Ask Why? Try Bud Dry"

ads asked why foreign films have to be so foreign.

The images were a parody of Bergman and Fellini. True,

these auteurs were Europeans themselves, but the sentiment

remains whoever is behind it. Over here they like all

that kind of "weird, boring, challenging stuff."

But if we Americans can get their respect, so it goes,

we must be doing something right.

|