|

Mayor Rudolph Guiliani wants to see a

"soaring monumental memorial" at the former World Trade Center site.

Agreed. We need something to stare down the graveyard of cement and steel that

buried so many. We need to see our collective hearts and minds at the site. Now

comes the hard part: How do you show the soul of a nation? How do you memorialize

lost lives? The late sculptor Isamu Noguchi said that sculpture should be experienced,

not just looked at. What image would do that?

The answer can make or

break the project. In 1947, New York mayor William O’Dwyer also sought a monument

to lost lives, the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Battle and the six million Jews

of Europe. But it was never built. No one could agree on the imagery. Proposals

were seen either as too morbid, too large or—unaccountably—too unrelated to American

history.

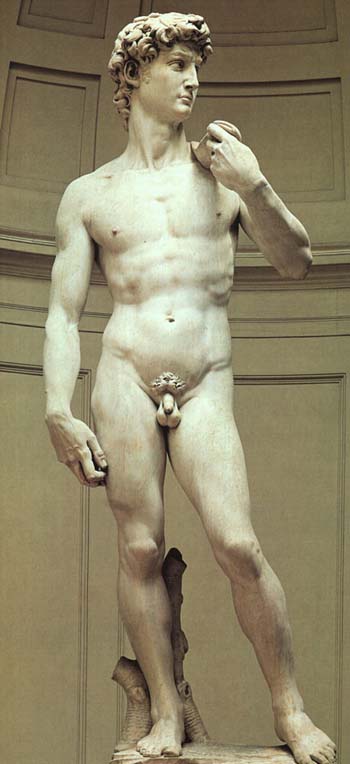

| Maybe

we ought to look to Europe for inspiration. People there have been at monuments

longer. Michelangelo’s "David" comes to mind. The sculpture was installed

in front of a seat of Florentine government, the Palazzo Vecchio more than 500

years ago, and it was a hit from the start. Vasari , an historian at the time,

says that "David" was intended as a symbol of liberty, signifying that

just as the shepherd boy protected his people and governed them justly as their

king, so whoever ruled Florence should vigorously defend the city and govern it

with justice.

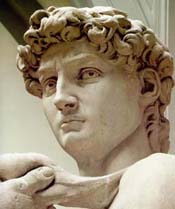

That’s his

opinion. But by calmly facing Goliath while furtively palming a stone in one hand

and with the sling flung casually over his shoulder, "David" comes across

more as an icon of governed might than warrior. The figure stands for reflection

before battle rather than the usual image of victory afterwards. That reining

in of inner strength can be seen in the figure’s steadfast and focused posture.

As well, "David" is everyman, a picture of human uncertainty, as

well as heroism. His gaze is not only intense, but also anxious. His furrowed

brow tells you that. Even from behind, there is an unsure gesture that surfaces

in a slight bend forward.  |

We

need a "David." He’s not a warmonger. Neither was the father of our

country, which is why the initial proposal to memorialize him never was erected.

The Continental Congress voted for an equestrian statue with General Washington

in Roman dress, his battle victories inscribed on the pedestal. Too monarch-like,

said the critics, and too militaristic. So America got a sculpture with no image.

It got a metaphor. A 555-foot obelisk on the Mall in Washington, D.C. the Washington

Monument presents a reaching gesture, a stark soaring, as if to new heights for

all Americans. It was supposed to be a national monument, but the Statue of Liberty,

erected a year later, assumed that mantel. The one-hundredth anniversary for each

tells that story. Compared to the highly publicized extravaganza for Miss Liberty,

the celebration of the Washington Monument went largely unnoticed. Where

does that leave the WTC memorial? If Miss Liberty is any example, probably the

WTC memorial should be figurative, but with the caveat that it not be maudlin.

We don’t want some visual counterpart to entries in the annual Bulwer-Lytonn Fiction

Contest, the bad-writing event that calls for the worst histrionic opening sentence

to an imagined novel, as in "It was a dark and stormy night." That

September 11 morning was our dark and stormy night. We need to counter it with

a monument—tall as a flagpole—that generates awe. We need a great presence neutral

in nothing, a reed in our storm. But likeable. We need a latter-day Michelangelo

for this one. |